Staying Power

This article originally appeared in the March 2005 issue of The Strad magazine.

by Colin Eatock

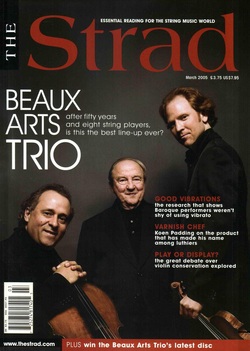

On stage, the Beaux Arts Trio huddle together, violinist Daniel Hope on the audience’s left, cellist Antonio Meneses close by on the right, and pianist Menahem Pressler just slightly behind. As they play, they maintain constant eye contact as phrases are carefully passed from one player to another. For expressive purposes, they have a full palette of timbres at their disposal, from delicate understatement to sparkling brilliance and powerful bravura. And yet the trio doesn’t “blend” in the sense that a fine string quartet does: their instruments are too dissimilar for that. Rather, what unifies the three musicians is a common sense of purpose.

Off stage, however, the members of the Beaux Arts Trio are a very diverse bunch. At 81 years of age, Pressler is the trio’s éminence grise: a small man with a strong will and boundless energy. Born in Germany and raised in Israel, he’s lived in America since 1947 but retains the continental manners of a bygone era. Antonio Meneses, 48 and currently in his seventh season with the trio, is a Brazilian who now lives in Basel, Switzerland. During an interview he’s formal and reserved, but in the pub after a concert he’s relaxed and laid back. And Daniel Hope, who joined the trio three years ago, is an Englishman whose current home is Amsterdam. At 30, he’s fresh-faced and energetic, with a flare for grandness: he was recently married in a lavish ceremony at Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace.

Yet despite differences in age and background, they get on remarkably well. Pressler seems to enjoy the company of younger people – a good thing, as he has lived longer than the two string players together. And both Meneses and Hope feel honoured to be working with a musician of Pressler’s experience. “There’s an art behind the balance of a piano trio,” observes Hope, “and that’s where Menahem Pressler is a master. That’s something I’ve learned from him.” Adds Meneses: “To play these pieces with someone who knows them as intimately as he does has opened my eyes and ears.”

Rehearsals, says Hope, can be intense. “On a travel day, we’ll meet three hours before the concert, and rehearse right up to the concert. If we have whole days, then we will do sizeable four- or five-hour rehearsals. They’re very detailed and technical, and may be a re-examination of the night before. Working on timing is what rehearsals on the road are about – balance and tempo, and everything that makes a piece tick, keeping it finely tuned.”

The Beaux Arts players opened their 50th season last August at the Ottawa International Chamber Music Festival (where I met the group), and are currently in the midst of a celebratory year. Fifty years is, of course, an astonishing lifespan for a chamber ensemble, and must surely be a longevity record for a professional piano trio. In the last half century, the Beaux Arts have given more than 5,000 performances (some estimates push the number as high as 7,000), and the ensemble has released around 60 recordings, mostly for Philips.

Over the years, there have been many changes to the trio’s membership. While Pressler has been the ensemble’s only pianist, there’s been an octet of string players. As well, the Beaux Arts have become thoroughly cosmopolitan – nowadays it’s impossible to describe the ensemble as “based” anywhere. Rehearsals are held around the world, wherever it’s most convenient: New York, Amsterdam, Hamburg – or in Bloomington, Indiana, where Pressler lives and teaches at Indiana University. But that wasn’t always the case: in the early years, the Beaux Arts were very much an American ensemble, playing mostly in locations throughout the US.

The trio originated in New York, where, in the mid-1950s, violinist Daniel Guilet, cellist Bernard Greenhouse and Pressler met in studio recording sessions. The original plan was to play a few concerts and make a record. But although conceived in urban Manhattan, it was at the bucolic Tanglewood Festival in Massachusetts was where the trio came into the world. Called upon on short notice to replace the Albeneri Trio, the Beaux Arts made their official concert debut at Tanglewood on July, 13, 1955. They played Beethoven – Op. 1 No 3, Op. 70 No. 1 (the “Ghost”) and Op. 97 (the “Archduke”) – and an impressed Charles Munch, then director of the Tanglewood Festival, declared the group the worthy successors of the Cortot-Thibaud-Casals Trio.

Soon, a few concerts became 70, and the ensemble began to look beyond America’s borders, appearing in Canada, Puerto Rico, and the UK. After hearing the Beaux Arts, William Glock of the BBC said he’d be pleased to broadcast them any time they were in Britain – thus initiating a relationship that has spanned five decades. (In February 2003, BBC Radio3 aired a five-part program on the Beaux Arts Trio, as part of the now-defunct “Artists in Focus” series.)

Commercial recording – the trio’s initial raison d’être – began with a 1957 release of Haydn’s Trio No. 1 in G Major and Mendelssohn’s D Minor Trio Op. 49, for the MGM label. In 1964 the group’s recording of Dvorak’s “Dumky” trio and Mendelssohn’s D Minor Trio, for Concert Hall Records, won a Grand Prix du Disque. Three years later they signed with Philips, initiating an outpouring of discs: two complete sets of Beethoven trios, plus two “Triple” concertos; multiple versions of trios by Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Dvorak, Brahms and Ravel; as well as releases of Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Fauré, Shostakovich and other composers. Bursting the bounds of the trio repertoire, they also recorded quartets and quintets by Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Dvorak, with guest artists.

The longevity of the Beaux Arts, and the trio’s vastly productive recording career, was in part driven by changes to the group’s membership. Every new configuration has, in a sense, been a different trio – and every change has offered potential both for renewal or for crisis. Some groupings have worked out better than others: the trio of violinist Ida Kavafian, cellist Peter Wiley and Pressler had “a more combustible chemistry” than previous combinations – as Tully Potter delicately put it in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

In 1998 Kavafian and Wiley both left the ensemble: Wiley to take the cello chair in the Guarneri Quartet, and Kavafian to found the piano quartet Opus One. At the time, Kavafian told the Arizona Daily Star, “I’m burned out a little bit. I want to step back, pay attention to my personal life.” And compounding the trio’s problems at this time was the implosion of the classical recording industry in the late 1990s, which brought to a close the Beaux Arts’ recording days with Philips.

Yet Pressler was determined to re-build – and his commitment made explicit something that had been implicit for years: he had become the group’s driving force, very much a first amongst equals. To fill the vacancies, Pressler approached Meneses and the Korean violinist Young-Uck Kim. The Brazilian cellist vividly recalls their first meeting: “We met in New York, and. he told us of all the things we would be part of – not only part of a very distinguished chamber music group, but of playing in places that I’d never played, and learning repertoire that is absolutely magnificent. He was able to make us dream about participating in the group – that it would be something beautiful. We were so charmed by Menahem that we agreed on the spot.”

Unfortunately, only four years later, Kim developed a painful condition in his neck. Surgery failed to remedy the problem, and he was forced to withdraw from the trio. Once again, a new violinist was needed – and Pressler began to wonder if he’d ever find the right person for the job. But things began to look up when Hope, a young Menuhin protégé with a thriving solo career, was asked to complete a Beaux Arts tour left in limbo by Kim’s sudden departure.

“As it happened,” says Hope, “I had a recording project that was cancelled, and I had three weeks empty in my diary. It was exactly the time that was needed. So my agent called me up and asked if I would be willing to play about 15 concerts, in all of the major halls in Europe, including the complete Beethoven trios, the Schubert E-flat, plus Haydn, Mozart, Schnittke, Schumann – the list was just endless. Once I’d recovered from the shock, I said yes.”

Hope continues: “So I flew to Basel, and Antonio and I spent about two days going through bowings and fingerings, just to see if we could find some kind of common ground. Two days later we flew to Lisbon and rehearsed day and night with Menahem for three days. It was like being thrown into boiling water, without any chance of getting out!” Once it became apparent that Kim would not be returning, Hope was asked to become a permanent member of the trio. “It was a fantastic offer for me,” says Hope with conviction, “I didn’t think twice.”

In many respects, the Beaux Arts’ current concert season is much like any other. In the fall the players toured Europe. Across the Atlantic, their engagements have taken them to such familiar venues as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Washington’s Library of Congress. But in the USA they’ve also played in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Urbana, Illinois – the sort of Mid-Western towns where they first made their name.

Yet the season also has a celebratory glow to it. In acknowledgement of Beaux Arts’ half-century, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw has commissioned two new works for the trio, from the German composer Jan Müller-Wieland and the Englishman Mark-Anthony Turnage. New music has not, historically, been the Beaux Arts’ strong suit, but the trio decided to work with these composers when Hope introduced them to the group. “Müller-Wieland had written a concerto and a piano quartet for me,” explains the violinist. “Mark-Anthony Turnage and I support the same football team – Arsenal – and he’d already begun work on a trio.”

In January, the trio gave the premiere of Müller-Wieland’s Schlaflied in the Concertgebouw’s Recital Hall, followed by performances in London, Paris, and other European cities. Turnage’s trio will be played in August, also at the Concertgebouw – as will a trio by György Kurtag, dedicated to Pressler. And in America, the Beaux Arts’ 50th season will be commemorated with a special concert on July 13 at the Tanglewood Festival, in Massachusetts, where the trio will perform the same all-Beethoven programme they played for their debut there, back in the summer of 1955.

Coinciding nicely with the Beaux Arts’ anniversary year has been a return to the recording studio – this time for Warner Classics. In the UK, Warner just released a new CD of the trio playing the Mendelssohn D Minor and the Dvorak “Dumky,” the Beaux Arts’ third disc pairing these works. Meanwhile, Philips has a four-disc box of historic recordings from the years 1967-1974 in the shops, containing trios by Mendelssohn, Robert and Clara Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Ives and Shostakovich. And Philips has also issued “A Fifty Year Celebration in Music,” a two-disc collection of trio movements.

For five decades, the Beaux Art has endured changes and challenges to emerge as the world’s most renowned piano trio. Indeed, the Beaux Arts has become a model for modern exponents of the genre – elevating the combination of piano, violin and cello to an artistic and professional status equal to any other kind of ensemble. Even Pressler acknowledges that the group has had its ups and downs: “There were always good threes, but not always the right three,” he told Chamber Music magazine two years ago. But through much perseverance and a little luck, the Beaux Arts has blossomed once again.

As for the future, Hope says the trio is currently planning their next two or three discs with Warner. “There are people there who are passionate about chamber music,” he enthuses. “It’s fantastic to find a company that’s willing to back things. Everything we’ve been told for years, that chamber music doesn’t sell, is simply not true! It can be extremely profitable.” As well, given the trio’s new-found interest in contemporary music, we can expect some more world premieres from the ensemble: next season they will play a new piece by Alexandra du Bois, a young composer currently studying at Indiana University.

Looking beyond next season, Pressler makes it clear that he has no plans to retire: “It will have to be told to me by the Great Director,” he says. “If my trio continues after me, and has these two young men, I will be happy.” (Hope shies away from the question of a post-Pressler Beaux Arts Trio altogether: “That’s something I prefer not to contemplate. It doesn’t bear any relevance on what we’re doing at the moment.”)

After five decades and thousands of concerts, Pressler can be excused for taking a moment to look back on past accomplishments: “The years with Guilet as our violinist were the learning years,” he reflects. “Our next violinist, Isidore Cohen, was with us for 23 years and, together with Greenhouse as cellist, the group was excellent. And the current trio is as good as any – it’s remarkably homogeneous. To be able to play in such an ensemble at my age is a privilege. And for that I am grateful.”

For that we should be grateful, too.

© Colin Eatock 2005

by Colin Eatock

On stage, the Beaux Arts Trio huddle together, violinist Daniel Hope on the audience’s left, cellist Antonio Meneses close by on the right, and pianist Menahem Pressler just slightly behind. As they play, they maintain constant eye contact as phrases are carefully passed from one player to another. For expressive purposes, they have a full palette of timbres at their disposal, from delicate understatement to sparkling brilliance and powerful bravura. And yet the trio doesn’t “blend” in the sense that a fine string quartet does: their instruments are too dissimilar for that. Rather, what unifies the three musicians is a common sense of purpose.

Off stage, however, the members of the Beaux Arts Trio are a very diverse bunch. At 81 years of age, Pressler is the trio’s éminence grise: a small man with a strong will and boundless energy. Born in Germany and raised in Israel, he’s lived in America since 1947 but retains the continental manners of a bygone era. Antonio Meneses, 48 and currently in his seventh season with the trio, is a Brazilian who now lives in Basel, Switzerland. During an interview he’s formal and reserved, but in the pub after a concert he’s relaxed and laid back. And Daniel Hope, who joined the trio three years ago, is an Englishman whose current home is Amsterdam. At 30, he’s fresh-faced and energetic, with a flare for grandness: he was recently married in a lavish ceremony at Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace.

Yet despite differences in age and background, they get on remarkably well. Pressler seems to enjoy the company of younger people – a good thing, as he has lived longer than the two string players together. And both Meneses and Hope feel honoured to be working with a musician of Pressler’s experience. “There’s an art behind the balance of a piano trio,” observes Hope, “and that’s where Menahem Pressler is a master. That’s something I’ve learned from him.” Adds Meneses: “To play these pieces with someone who knows them as intimately as he does has opened my eyes and ears.”

Rehearsals, says Hope, can be intense. “On a travel day, we’ll meet three hours before the concert, and rehearse right up to the concert. If we have whole days, then we will do sizeable four- or five-hour rehearsals. They’re very detailed and technical, and may be a re-examination of the night before. Working on timing is what rehearsals on the road are about – balance and tempo, and everything that makes a piece tick, keeping it finely tuned.”

The Beaux Arts players opened their 50th season last August at the Ottawa International Chamber Music Festival (where I met the group), and are currently in the midst of a celebratory year. Fifty years is, of course, an astonishing lifespan for a chamber ensemble, and must surely be a longevity record for a professional piano trio. In the last half century, the Beaux Arts have given more than 5,000 performances (some estimates push the number as high as 7,000), and the ensemble has released around 60 recordings, mostly for Philips.

Over the years, there have been many changes to the trio’s membership. While Pressler has been the ensemble’s only pianist, there’s been an octet of string players. As well, the Beaux Arts have become thoroughly cosmopolitan – nowadays it’s impossible to describe the ensemble as “based” anywhere. Rehearsals are held around the world, wherever it’s most convenient: New York, Amsterdam, Hamburg – or in Bloomington, Indiana, where Pressler lives and teaches at Indiana University. But that wasn’t always the case: in the early years, the Beaux Arts were very much an American ensemble, playing mostly in locations throughout the US.

The trio originated in New York, where, in the mid-1950s, violinist Daniel Guilet, cellist Bernard Greenhouse and Pressler met in studio recording sessions. The original plan was to play a few concerts and make a record. But although conceived in urban Manhattan, it was at the bucolic Tanglewood Festival in Massachusetts was where the trio came into the world. Called upon on short notice to replace the Albeneri Trio, the Beaux Arts made their official concert debut at Tanglewood on July, 13, 1955. They played Beethoven – Op. 1 No 3, Op. 70 No. 1 (the “Ghost”) and Op. 97 (the “Archduke”) – and an impressed Charles Munch, then director of the Tanglewood Festival, declared the group the worthy successors of the Cortot-Thibaud-Casals Trio.

Soon, a few concerts became 70, and the ensemble began to look beyond America’s borders, appearing in Canada, Puerto Rico, and the UK. After hearing the Beaux Arts, William Glock of the BBC said he’d be pleased to broadcast them any time they were in Britain – thus initiating a relationship that has spanned five decades. (In February 2003, BBC Radio3 aired a five-part program on the Beaux Arts Trio, as part of the now-defunct “Artists in Focus” series.)

Commercial recording – the trio’s initial raison d’être – began with a 1957 release of Haydn’s Trio No. 1 in G Major and Mendelssohn’s D Minor Trio Op. 49, for the MGM label. In 1964 the group’s recording of Dvorak’s “Dumky” trio and Mendelssohn’s D Minor Trio, for Concert Hall Records, won a Grand Prix du Disque. Three years later they signed with Philips, initiating an outpouring of discs: two complete sets of Beethoven trios, plus two “Triple” concertos; multiple versions of trios by Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Dvorak, Brahms and Ravel; as well as releases of Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Fauré, Shostakovich and other composers. Bursting the bounds of the trio repertoire, they also recorded quartets and quintets by Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Dvorak, with guest artists.

The longevity of the Beaux Arts, and the trio’s vastly productive recording career, was in part driven by changes to the group’s membership. Every new configuration has, in a sense, been a different trio – and every change has offered potential both for renewal or for crisis. Some groupings have worked out better than others: the trio of violinist Ida Kavafian, cellist Peter Wiley and Pressler had “a more combustible chemistry” than previous combinations – as Tully Potter delicately put it in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

In 1998 Kavafian and Wiley both left the ensemble: Wiley to take the cello chair in the Guarneri Quartet, and Kavafian to found the piano quartet Opus One. At the time, Kavafian told the Arizona Daily Star, “I’m burned out a little bit. I want to step back, pay attention to my personal life.” And compounding the trio’s problems at this time was the implosion of the classical recording industry in the late 1990s, which brought to a close the Beaux Arts’ recording days with Philips.

Yet Pressler was determined to re-build – and his commitment made explicit something that had been implicit for years: he had become the group’s driving force, very much a first amongst equals. To fill the vacancies, Pressler approached Meneses and the Korean violinist Young-Uck Kim. The Brazilian cellist vividly recalls their first meeting: “We met in New York, and. he told us of all the things we would be part of – not only part of a very distinguished chamber music group, but of playing in places that I’d never played, and learning repertoire that is absolutely magnificent. He was able to make us dream about participating in the group – that it would be something beautiful. We were so charmed by Menahem that we agreed on the spot.”

Unfortunately, only four years later, Kim developed a painful condition in his neck. Surgery failed to remedy the problem, and he was forced to withdraw from the trio. Once again, a new violinist was needed – and Pressler began to wonder if he’d ever find the right person for the job. But things began to look up when Hope, a young Menuhin protégé with a thriving solo career, was asked to complete a Beaux Arts tour left in limbo by Kim’s sudden departure.

“As it happened,” says Hope, “I had a recording project that was cancelled, and I had three weeks empty in my diary. It was exactly the time that was needed. So my agent called me up and asked if I would be willing to play about 15 concerts, in all of the major halls in Europe, including the complete Beethoven trios, the Schubert E-flat, plus Haydn, Mozart, Schnittke, Schumann – the list was just endless. Once I’d recovered from the shock, I said yes.”

Hope continues: “So I flew to Basel, and Antonio and I spent about two days going through bowings and fingerings, just to see if we could find some kind of common ground. Two days later we flew to Lisbon and rehearsed day and night with Menahem for three days. It was like being thrown into boiling water, without any chance of getting out!” Once it became apparent that Kim would not be returning, Hope was asked to become a permanent member of the trio. “It was a fantastic offer for me,” says Hope with conviction, “I didn’t think twice.”

In many respects, the Beaux Arts’ current concert season is much like any other. In the fall the players toured Europe. Across the Atlantic, their engagements have taken them to such familiar venues as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Washington’s Library of Congress. But in the USA they’ve also played in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Urbana, Illinois – the sort of Mid-Western towns where they first made their name.

Yet the season also has a celebratory glow to it. In acknowledgement of Beaux Arts’ half-century, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw has commissioned two new works for the trio, from the German composer Jan Müller-Wieland and the Englishman Mark-Anthony Turnage. New music has not, historically, been the Beaux Arts’ strong suit, but the trio decided to work with these composers when Hope introduced them to the group. “Müller-Wieland had written a concerto and a piano quartet for me,” explains the violinist. “Mark-Anthony Turnage and I support the same football team – Arsenal – and he’d already begun work on a trio.”

In January, the trio gave the premiere of Müller-Wieland’s Schlaflied in the Concertgebouw’s Recital Hall, followed by performances in London, Paris, and other European cities. Turnage’s trio will be played in August, also at the Concertgebouw – as will a trio by György Kurtag, dedicated to Pressler. And in America, the Beaux Arts’ 50th season will be commemorated with a special concert on July 13 at the Tanglewood Festival, in Massachusetts, where the trio will perform the same all-Beethoven programme they played for their debut there, back in the summer of 1955.

Coinciding nicely with the Beaux Arts’ anniversary year has been a return to the recording studio – this time for Warner Classics. In the UK, Warner just released a new CD of the trio playing the Mendelssohn D Minor and the Dvorak “Dumky,” the Beaux Arts’ third disc pairing these works. Meanwhile, Philips has a four-disc box of historic recordings from the years 1967-1974 in the shops, containing trios by Mendelssohn, Robert and Clara Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Ives and Shostakovich. And Philips has also issued “A Fifty Year Celebration in Music,” a two-disc collection of trio movements.

For five decades, the Beaux Art has endured changes and challenges to emerge as the world’s most renowned piano trio. Indeed, the Beaux Arts has become a model for modern exponents of the genre – elevating the combination of piano, violin and cello to an artistic and professional status equal to any other kind of ensemble. Even Pressler acknowledges that the group has had its ups and downs: “There were always good threes, but not always the right three,” he told Chamber Music magazine two years ago. But through much perseverance and a little luck, the Beaux Arts has blossomed once again.

As for the future, Hope says the trio is currently planning their next two or three discs with Warner. “There are people there who are passionate about chamber music,” he enthuses. “It’s fantastic to find a company that’s willing to back things. Everything we’ve been told for years, that chamber music doesn’t sell, is simply not true! It can be extremely profitable.” As well, given the trio’s new-found interest in contemporary music, we can expect some more world premieres from the ensemble: next season they will play a new piece by Alexandra du Bois, a young composer currently studying at Indiana University.

Looking beyond next season, Pressler makes it clear that he has no plans to retire: “It will have to be told to me by the Great Director,” he says. “If my trio continues after me, and has these two young men, I will be happy.” (Hope shies away from the question of a post-Pressler Beaux Arts Trio altogether: “That’s something I prefer not to contemplate. It doesn’t bear any relevance on what we’re doing at the moment.”)

After five decades and thousands of concerts, Pressler can be excused for taking a moment to look back on past accomplishments: “The years with Guilet as our violinist were the learning years,” he reflects. “Our next violinist, Isidore Cohen, was with us for 23 years and, together with Greenhouse as cellist, the group was excellent. And the current trio is as good as any – it’s remarkably homogeneous. To be able to play in such an ensemble at my age is a privilege. And for that I am grateful.”

For that we should be grateful, too.

© Colin Eatock 2005