Culture Wars at the CBC

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Queen’s Quarterly, a journal published by Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada.

by Colin Eatock

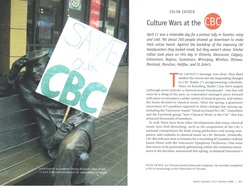

April 11 was a miserable day for a protest rally in Toronto: rainy and cold. Yet about 200 people showed up downtown to make their voices heard. Against the backdrop of the imposing CBC headquarters they looked small, but they weren’t alone. Similar rallies took place on this day in Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Windsor, Ottawa, Montreal, Moncton, Halifax and St. John’s.

The crowd’s message was clear: they liked neither the recent nor the impending changes to CBC Radio 2’s progamming schedule. Since its founding, Radio 2 has been largely (although never entirely) a classical music broadcaster – but that will soon be a thing of the past, as corporation managers press forward with plans to introduce a wider variety of musical genres, and cut back on the hours devoted to classical music. Since the spring, a grassroots movement of Canadians opposed to these changes has sprung up, including the Vancouver-based “Stand on Guard for CBC” committee, and the Facebook group “Save Classical Music at the CBC” that has attracted thousands of members.

As well, there have been other developments that many classical-music fans find disturbing, such as the suspension of the CBC’s national competitions for both young performers and young composers, and cutbacks to classical music on CBC Records. (Ironically, CBC Records just won a Grammy for a recording of Canadian violinist James Ehnes with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra.) One issue that seems to be particularly galvanizing within the resistance movement is the decision, announced this spring, to disband Vancouver’s CBC Radio Orchestra. One protester waved a sign that proclaimed, “My Canada includes the CBC Radio Orchestra.”

To those well acquainted with Toronto’s classical-music scene, there were some familiar faces in the crowd: performers, composers, musicians’ managers, and even a few former employees of the corporation. Speakers included James Rolfe, president of the Canadian League of Composers, choral conductor Lydia Adams, and Globe and Mail columnist Russell Smith. Stated Smith:

“I think one can’t help but notice that there is a disconnect between what CBC Radio says it is doing and what it actually does. The spokesmen make soothing noises: of course we are not turning against classical music, they say. We are still fully committed to it; it remains ‘at the core’ of the programming. By this they mean pretty much the opposite: they mean that it will be removed from the most popular programs – at breakfast, during the drive home, and during the evening.”

However, most of the protesters weren’t professional musicians or pundits, but simply fans of CBC Radio 2 (as it used to be). Predominantly, they were well educated, middle-class and at least middle-aged: not the sort of people who routinely show up at public protests. Conspicuously absent was any response from the CBC: skittish in the face of controversy, staffers remained in their building.

It’s easy to caricature both sides of this debate. On one hand we have a gaggle of backwards-looking, lily-white, octogenarian alarmists, for whom European high culture serves as a kind of religion. They live in gated communities, and are so out of touch with Canada today that they can’t begin to grasp how out of touch they are. On the other hand we have a clutch of trendy, urbane, latte-sipping bureaucrats who intend to gradually transform Radio 2 into a bland easy-listening network. They know nothing about classical music, are damn proud of it, and desperately want to be cool. To the resistance movement, the CBC bureaucrats are “arrogant”; to the bureaucrats, the resisters are “elitist.”

Unfortunately, some of the things that have been said and done in this ongoing culture battle have only borne out these stereotypes. There are indeed a number of “fundamentalist” resisters who evidently feel that Radio 2 belongs to them alone, and who will have no truck with any kind of music that isn’t classical. They do not disguise their contempt for the jazz, folk, roots, R&B, and singer-songwriter genres the CBC plans to broadcast: to them it is all simply “pop music,” and its inclusion on Radio 2 constitutes a “dumbing down” of the network. One Vancouver-based concert pianist has denounced progamming changes at Radio 2 as “cultural genocide.”

As for the CBC, it has taken refuge behind carefully crafted statements, attempting to brush aside the controversy with such glib remarks as “We choose to take a positive view of the concern about our programming.” And on March 29 the CBC purchased the first in a series of a big newspaper advertisements, promoting its next round of changes, scheduled to hit the airwaves in September. “We applaud the new CBC Radio 2,” stated the ad, which was endorsed by several dozen representatives of “the music industry.” (None were classical musicians; rather, they were composers, performers and producers of non-classical genres, who all stand to gain from Radio 2’s new format.) The implied messages were clear: the changes in programming are a done deal; and the CBC is quite willing to abandon its current Radio 2 audience in its quest for a new one.

The fate of Radio 2 – a network that Canadians have either quietly enjoyed or completely ignored for decades – has become the focus of a public debate. (I’ll offer my own views at the end of this article.) Moreover, this culture battle highlights broader questions. Who decides what the CBC broadcasts? What sort of audience should Radio 2 be trying to attract? And what does this debate say about the position of classical music in Canadian society today? But first, let’s step back a few years, to see how reinventing Radio 2 became an agenda item at the CBC.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was created in 1936. Its aims and objectives have changed over the years: its current mandate is the Broadcasting Act of 1991, which directs CBC to “provide radio and television services incorporating a wide range of progamming that informs, enlightens and entertains.” Radio 2 (first called CBC FM, then CBC Stereo) has been on the air since 1964. Although it was never officially defined as a classical-music service, for most of its history that has been the virtual reality. For four decades, Radio 2 didn’t just broadcast classical music: the network nurtured it, supporting Canada’s classical musicians and cultivating a taste for the art they practiced.

In 2004, the CBC commissioned a study to find out what it could about Canadian attitudes towards the corporation. It was an extensive project that involved written surveys and face-to-face interviews with people across the country. The end-result of this research was a document entitled The CBC Arts & Culture Research Study, and in its pages one may find statistical proofs for many things everybody already knows: Canadian society is becoming more ethnically diverse, most Canadians own a DVD player; most Canadians have internet access – and the especially shocking revelation that most Canadians (especially younger people) don’t listen to classical music. In conclusion, the study made the highly debatable claim that the CBC’s own staff feels that arts and culture programming should be “more accessible, engaging and lighter in tone.”

Subsequently, a CBC management team – including Head of Radio Music Mark Steinmetz, Executive Director of Programming Jennifer McGuire and Executive Vice-President of English Services Richard Stursberg – put together a three-stage plan to reinvent Radio 2. The first stage of this plan focused on the evening schedule, and was executed in March 2007. The classical programs “Music for a While” and “In Performance” were replaced with “Tonic,” “Canada Live,” and “The Signal.” “Tonic” is a jazz show; “Canada Live” generally features bands performing in clubs and lounges; and “The Signal” plays a mix of non-commercial musics (some of which could be described as classical, some of which couldn’t).

Also at this time, the CBC cancelled “Two New Hours,” a weekly showcase devoted exclusively to the classical music of our time, broadcast on Sunday nights. This did not sit at all well with the Canadian League of Composers. But when Canada’s classical composers protested the decision as an attack on contemporary music, they found themselves drawn into a debate with CBC management about what the phrase “contemporary music” means. To the composers, it meant something quite specific: new music that, in its aesthetic goals, creative methods or historical lineage, is somehow connected to Western classical-music traditions. However, the CBC managers took the position that “contemporary music” simply means any kind of recently created music: pop, rock, jazz, whatever.

The changes continued. In September 2007 CBC management revised the weekend daytime schedule: “Symphony Hall” and “The Singer and the Song” were cancelled, among other revisions to the schedule. The third and final stage in the transformation of Radio 2 was announced in March 2008 (although the plan won’t be implemented until the fall). These changes will effect weekdays: the morning show, “Music and Company,” will be axed; as well as the popular late-afternoon show, “Disc Drive.” As of September 2008, classical music – which once dominated Radio 2’s programming – will be reduced to a five-hour time-slot in the middle of the day, between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm. It was also in March that the CBC announced the CBC Vancouver Radio Orchestra would be disbanded.

In response to these announcements, disgruntled classical music fans started to organize and speak out. One such listener was Peter McGillivray, who hit upon the idea of establishing a Facebook group called “Save Classical Music at the CBC.” Within two weeks the group had about 2,000 members, and within two months that number had grown to 15,000.

McGillivray is a professional singer – and was, in fact, a prizewinner in the CBC Young Performers Competition (the last one ever held, in 2003). So it’s not surprising that he feels both a personal and professional connection to the CBC. “I credit the CBC competition with launching my career,” he says. “I was fresh out of opera school and $40,000 in debt. I had my debt wiped out, and had opportunities to perform all over the country.”

He continues, offering his own views on what’s happening to Radio 2. “The changes are being driven by the CBC managers who are not interested in classical music. They don’t understand the cultural aspects of their decisions – they think they’re there to reach and entertain the widest possible audience. The other thing that’s driving these decisions is the recording industry. The commercial record companies are pressuring the CBC to open the floodgates.”

McGillivray is by no means alone, within his profession, in his antipathy to the changes to Radio 2. On the other hand, classical musicians who are prepared to endorse the CBC’s decisions are as rare as hen’s teeth. The Toronto composer Christos Hatzis has come forward in support of the new Radio 2, urging his colleagues to “remain in the forefront of cultural change and not the reactionary shadows of constantly invoking the status quo.” (He subsequently appeared in one of the CBC’s newspaper ads in April endorsing the corporation’s programming decisions.) There may be a few others who share Hatzis’ views – but, overall, there is a remarkably strong consensus of opposition to the new Radio 2 among classical musicians.

Some “ordinary Canadians” have also publicly expressed their concerns. James Wooten is not a musician; he works in the high-tech sector, in Ottawa. But he became so frustrated with CBC Radio 2 that he started his own blog: “CBC Radio 2 and Me,” to document his correspondence with CBC managers. “The CBC is a corporation that is completely opaque,” he charges. “You have to rely on them to tell the public if what they’re doing is successful. And Radio 2 management doesn’t seem to encourage people to make comments.”

It may be that the most enthusiastic (or, at least, the most determined) supporters of the changes to Radio 2 are the people who are making the changes. These may be found within the CBC’s managerial ranks – but they are not, generally, the announcers, producers and technicians for Radio 2’s programs. Unfortunately, the people who actually put the shows together are not very happy these days. They often refuse to publicly express their views on the subject of Radio 2, fearing this would endanger their careers. Some are voting with their feet, choosing to accept early retirement packages. One classical programmer, who cautiously agreed to talk to me (anonymously and off site), was dismissive of the managers who are behind the plans to overhaul Radio 2: “If these people didn’t change things, they wouldn’t have jobs.”

However, one of the managers behind the changes, Mark Steinmetz, agrees to talk about programming – although I suspect there are things he’d rather do. Indeed, it soon becomes apparent that he’s getting a little tired of defending Radio 2’s policies. “People say we’re intransigent because we’re not not changing,” he says with a touch of exasperation. “But we’ve talked to hundreds of stakeholders.”

According to statistics, Steinmetz says, only a small minority of Canadians – between 3 and 4 percent – tune in to Radio 2 in a typical week. As well, he cites research that indicates the aging Radio 2 audience is not being replaced by younger listeners. “We want to see a sustainable audience,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with older listeners, but what’s not good is that there’s no audience coming in behind them.” He also explains that audience-share varies considerably from one region of Canada to another. “Radio 2 has a much higher share in British Columbia or Ottawa than in Newfoundland, where it barely registers at all.”

And he points to the Broadcast Act. “Our goal is to adhere to our mandate,” he states, “which is often flung in my face by people who don’t agree with the changes. Currently, we’re not using the public space to reflect the broad range of music-making in this country.”

Steinmetz flatly denies that it’s the CBC’s intention to entirely eliminate classical music from Radio 2, and he also denies that external pressure from irate listeners will sway the corporation in its programming decisions. And while he doesn’t deny the number of broadcast-hours devoted to classical music have been substantially reduced in the last two years, he doesn’t see this as the issue. “It’s not about tonnage,” he insists. “The future of classical music isn’t going to hinge on playing it all day. It’s about creating engaging programming.”

As for the CBC Orchestra, he says that the decision to disband it was difficult, and made for purely economic reasons: the money can be put to better use elsewhere. “We will be upping the commissioning budget for contemporary music,” he assures me. What Steinmetz would rather talk about are some of the innovations that will soon be available from the CBC: streamed music on the internet, allowing listeners to hear classical music, and other genres, whenever they want; and downloadable concerts available for a year after an event is recorded. (What he doesn’t say is that Canadians living in rural areas where high-speed internet is not available will find it hard to access these services.)

Meanwhile, those opposed to the reduction of classical music at the CBC continue to organize and express their concerns. The resistance movement is strongest on the West Coast, where the CBC Vancouver Orchestra has been based for 70 years. But there are vocal groups in other regions, and on May 24 another round of rallies was held in cities across the country. The movement has organized its own publicity campaign; and has called upon both the CRTC and the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage to examine the issue. The debate may heat up again in the autumn, when (or if) the third round of changes to Radio 2 is implemented – and as the CBC Vancouver Orchestra’s final concert, on November 16, draws nigh.

I said I would conclude with my own opinions, so here they are. First, I should explain that although I’ve written about classical music for the Globe and Mail and other publications from time to time, I don’t consider myself a “fundamentalist”: I’m glad to say that there are other kinds of music I enjoy and respect. Also, I don’t subscribe to the view that the only kind of music worthy of the name “contemporary” is contemporary classical music.

However, I fear that the CBC is making a grave error in trying to mix such a wide array of musical styles and genres on a single radio network. Most radio listeners want the kind of music they want when they want it: when they want country music, they tune to a country station; when they want classical, they tune to a classical station. Private broadcasters understand how well-defined people’s musical tastes can be: a commercial radio station will generally stay within a clear, narrowly defined aesthetic, in order to carve out a distinctive voice in the marketplace. Steinmetz told me that “people are tired formatted radio.” But if he is wrong, Radio 2 could end up in a bad way: losing the loyal audience it has built up over the years, while failing to attract new listeners.

While I’m concerned about the reduction of classical music on Radio 2, I’m also disturbed by some of the other cuts to classical music at the CBC. The elimination of the national competitions for young performers and young composers is a blow to classical music in Canada – and it’s not yet clear how they will be effectively replaced. Without new releases from CBC Records, Canada’s classical musicians will lose a prestigious outlet for their talents. And the disbanding of the CBC Vancouver Orchestra will silence an excellent and unique ensemble that costs each Canadian a few pennies per year.

However, this isn’t just about a radio network or an orchestra – it’s also about the position of classical music in our society. Of late, of this once-honoured musical art has been losing ground in the forum of public perception. Newspapers have reduced coverage of classical music. Record stores that sell classical CDs are rare and getting rarer. Music education has been cut back in many schools. The art form is certainly not dying (on the contrary, there are many signs of vitality), but its “presence” is being eroded. Classical-music enthusiasts have been feeling marginalized for some time – and this probably helps to explain why the changes at Radio 2 have become such a sore point. The debate over the CBC’s policies is a struggle to determine if classical music can retain a place in Canada’s mainstream culture, or whether it will be relegated to the status of a “niche interest.”

And there’s even more at stake. In Canada, our governments offer a wide range of services – so wide that it would be impossible for any individual citizen to make use of all of them. This approach to providing services is founded on a very Canadian de-facto social contract: “If it’s not for you, it’s for someone else.” However, the changes to Radio 2 are ideologically grounded on the belief that all government-funded services should somehow be for everyone – and not just available to all, but to the taste of all. What else might we measure by this majoritarian yardstick? How many Canadians make use of public libraries, amateur sports programs, or national parks? Does the art hanging in the National Gallery reflect the full diversity of artistic expression in Canada? How does the Coast Guard benefit the people of Alberta and Saskatchewan?

And what about the CBC’s Radio 3 service, available on the internet and on Sirius? It plays “alt-pop” (alternative popular music) and “indie-rock” (independent rock music), and it’s not very diverse. Perhaps the Canadian singer-songwriters who the CBC’s managers claim are unduly neglected would find a happier home here, rather than shoehorned in with classical music on Radio 2. (Until recently, the CBC aspired to make Radio 3 into a full-fledged on-air network, but these plans were dropped due to lack of funding.)

Canada’s classical music community has often proven itself determined and resilient. Our orchestras struggle to survive – and, against all odds, they do. It took more than thirty years of lobbying for Toronto to get a proper opera house, but now it is built. Every summer a new chamber-music festival springs up somewhere. And our music faculties and conservatories continue to attract talented and enthusiastic students of classical music.

The CBC likes to give the impression that resistance is futile – that China will free Tibet before the corporation’s plans will be even slightly altered. But the decisions of the CBC’s managers are not carved in stone. Although they may chose to blithely overlook thousands of names on Facebook, they would find the concerns of elected officials much harder to ignore. (Despite the corporation’s “arm’s length” relationship with the federal government, the CBC knows where its bread is buttered.) To succeed, the resistance movement needs political support.

With intelligent, strategic persistence, and some allies in high places, it may still be possible for the CBC’s policies to be changed. However, if Canadians who care about classical music fail to speak up at this time, then perhaps they deserve to be marginalized.

© Copyright Colin Eatock 2008

by Colin Eatock

April 11 was a miserable day for a protest rally in Toronto: rainy and cold. Yet about 200 people showed up downtown to make their voices heard. Against the backdrop of the imposing CBC headquarters they looked small, but they weren’t alone. Similar rallies took place on this day in Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Windsor, Ottawa, Montreal, Moncton, Halifax and St. John’s.

The crowd’s message was clear: they liked neither the recent nor the impending changes to CBC Radio 2’s progamming schedule. Since its founding, Radio 2 has been largely (although never entirely) a classical music broadcaster – but that will soon be a thing of the past, as corporation managers press forward with plans to introduce a wider variety of musical genres, and cut back on the hours devoted to classical music. Since the spring, a grassroots movement of Canadians opposed to these changes has sprung up, including the Vancouver-based “Stand on Guard for CBC” committee, and the Facebook group “Save Classical Music at the CBC” that has attracted thousands of members.

As well, there have been other developments that many classical-music fans find disturbing, such as the suspension of the CBC’s national competitions for both young performers and young composers, and cutbacks to classical music on CBC Records. (Ironically, CBC Records just won a Grammy for a recording of Canadian violinist James Ehnes with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra.) One issue that seems to be particularly galvanizing within the resistance movement is the decision, announced this spring, to disband Vancouver’s CBC Radio Orchestra. One protester waved a sign that proclaimed, “My Canada includes the CBC Radio Orchestra.”

To those well acquainted with Toronto’s classical-music scene, there were some familiar faces in the crowd: performers, composers, musicians’ managers, and even a few former employees of the corporation. Speakers included James Rolfe, president of the Canadian League of Composers, choral conductor Lydia Adams, and Globe and Mail columnist Russell Smith. Stated Smith:

“I think one can’t help but notice that there is a disconnect between what CBC Radio says it is doing and what it actually does. The spokesmen make soothing noises: of course we are not turning against classical music, they say. We are still fully committed to it; it remains ‘at the core’ of the programming. By this they mean pretty much the opposite: they mean that it will be removed from the most popular programs – at breakfast, during the drive home, and during the evening.”

However, most of the protesters weren’t professional musicians or pundits, but simply fans of CBC Radio 2 (as it used to be). Predominantly, they were well educated, middle-class and at least middle-aged: not the sort of people who routinely show up at public protests. Conspicuously absent was any response from the CBC: skittish in the face of controversy, staffers remained in their building.

It’s easy to caricature both sides of this debate. On one hand we have a gaggle of backwards-looking, lily-white, octogenarian alarmists, for whom European high culture serves as a kind of religion. They live in gated communities, and are so out of touch with Canada today that they can’t begin to grasp how out of touch they are. On the other hand we have a clutch of trendy, urbane, latte-sipping bureaucrats who intend to gradually transform Radio 2 into a bland easy-listening network. They know nothing about classical music, are damn proud of it, and desperately want to be cool. To the resistance movement, the CBC bureaucrats are “arrogant”; to the bureaucrats, the resisters are “elitist.”

Unfortunately, some of the things that have been said and done in this ongoing culture battle have only borne out these stereotypes. There are indeed a number of “fundamentalist” resisters who evidently feel that Radio 2 belongs to them alone, and who will have no truck with any kind of music that isn’t classical. They do not disguise their contempt for the jazz, folk, roots, R&B, and singer-songwriter genres the CBC plans to broadcast: to them it is all simply “pop music,” and its inclusion on Radio 2 constitutes a “dumbing down” of the network. One Vancouver-based concert pianist has denounced progamming changes at Radio 2 as “cultural genocide.”

As for the CBC, it has taken refuge behind carefully crafted statements, attempting to brush aside the controversy with such glib remarks as “We choose to take a positive view of the concern about our programming.” And on March 29 the CBC purchased the first in a series of a big newspaper advertisements, promoting its next round of changes, scheduled to hit the airwaves in September. “We applaud the new CBC Radio 2,” stated the ad, which was endorsed by several dozen representatives of “the music industry.” (None were classical musicians; rather, they were composers, performers and producers of non-classical genres, who all stand to gain from Radio 2’s new format.) The implied messages were clear: the changes in programming are a done deal; and the CBC is quite willing to abandon its current Radio 2 audience in its quest for a new one.

The fate of Radio 2 – a network that Canadians have either quietly enjoyed or completely ignored for decades – has become the focus of a public debate. (I’ll offer my own views at the end of this article.) Moreover, this culture battle highlights broader questions. Who decides what the CBC broadcasts? What sort of audience should Radio 2 be trying to attract? And what does this debate say about the position of classical music in Canadian society today? But first, let’s step back a few years, to see how reinventing Radio 2 became an agenda item at the CBC.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was created in 1936. Its aims and objectives have changed over the years: its current mandate is the Broadcasting Act of 1991, which directs CBC to “provide radio and television services incorporating a wide range of progamming that informs, enlightens and entertains.” Radio 2 (first called CBC FM, then CBC Stereo) has been on the air since 1964. Although it was never officially defined as a classical-music service, for most of its history that has been the virtual reality. For four decades, Radio 2 didn’t just broadcast classical music: the network nurtured it, supporting Canada’s classical musicians and cultivating a taste for the art they practiced.

In 2004, the CBC commissioned a study to find out what it could about Canadian attitudes towards the corporation. It was an extensive project that involved written surveys and face-to-face interviews with people across the country. The end-result of this research was a document entitled The CBC Arts & Culture Research Study, and in its pages one may find statistical proofs for many things everybody already knows: Canadian society is becoming more ethnically diverse, most Canadians own a DVD player; most Canadians have internet access – and the especially shocking revelation that most Canadians (especially younger people) don’t listen to classical music. In conclusion, the study made the highly debatable claim that the CBC’s own staff feels that arts and culture programming should be “more accessible, engaging and lighter in tone.”

Subsequently, a CBC management team – including Head of Radio Music Mark Steinmetz, Executive Director of Programming Jennifer McGuire and Executive Vice-President of English Services Richard Stursberg – put together a three-stage plan to reinvent Radio 2. The first stage of this plan focused on the evening schedule, and was executed in March 2007. The classical programs “Music for a While” and “In Performance” were replaced with “Tonic,” “Canada Live,” and “The Signal.” “Tonic” is a jazz show; “Canada Live” generally features bands performing in clubs and lounges; and “The Signal” plays a mix of non-commercial musics (some of which could be described as classical, some of which couldn’t).

Also at this time, the CBC cancelled “Two New Hours,” a weekly showcase devoted exclusively to the classical music of our time, broadcast on Sunday nights. This did not sit at all well with the Canadian League of Composers. But when Canada’s classical composers protested the decision as an attack on contemporary music, they found themselves drawn into a debate with CBC management about what the phrase “contemporary music” means. To the composers, it meant something quite specific: new music that, in its aesthetic goals, creative methods or historical lineage, is somehow connected to Western classical-music traditions. However, the CBC managers took the position that “contemporary music” simply means any kind of recently created music: pop, rock, jazz, whatever.

The changes continued. In September 2007 CBC management revised the weekend daytime schedule: “Symphony Hall” and “The Singer and the Song” were cancelled, among other revisions to the schedule. The third and final stage in the transformation of Radio 2 was announced in March 2008 (although the plan won’t be implemented until the fall). These changes will effect weekdays: the morning show, “Music and Company,” will be axed; as well as the popular late-afternoon show, “Disc Drive.” As of September 2008, classical music – which once dominated Radio 2’s programming – will be reduced to a five-hour time-slot in the middle of the day, between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm. It was also in March that the CBC announced the CBC Vancouver Radio Orchestra would be disbanded.

In response to these announcements, disgruntled classical music fans started to organize and speak out. One such listener was Peter McGillivray, who hit upon the idea of establishing a Facebook group called “Save Classical Music at the CBC.” Within two weeks the group had about 2,000 members, and within two months that number had grown to 15,000.

McGillivray is a professional singer – and was, in fact, a prizewinner in the CBC Young Performers Competition (the last one ever held, in 2003). So it’s not surprising that he feels both a personal and professional connection to the CBC. “I credit the CBC competition with launching my career,” he says. “I was fresh out of opera school and $40,000 in debt. I had my debt wiped out, and had opportunities to perform all over the country.”

He continues, offering his own views on what’s happening to Radio 2. “The changes are being driven by the CBC managers who are not interested in classical music. They don’t understand the cultural aspects of their decisions – they think they’re there to reach and entertain the widest possible audience. The other thing that’s driving these decisions is the recording industry. The commercial record companies are pressuring the CBC to open the floodgates.”

McGillivray is by no means alone, within his profession, in his antipathy to the changes to Radio 2. On the other hand, classical musicians who are prepared to endorse the CBC’s decisions are as rare as hen’s teeth. The Toronto composer Christos Hatzis has come forward in support of the new Radio 2, urging his colleagues to “remain in the forefront of cultural change and not the reactionary shadows of constantly invoking the status quo.” (He subsequently appeared in one of the CBC’s newspaper ads in April endorsing the corporation’s programming decisions.) There may be a few others who share Hatzis’ views – but, overall, there is a remarkably strong consensus of opposition to the new Radio 2 among classical musicians.

Some “ordinary Canadians” have also publicly expressed their concerns. James Wooten is not a musician; he works in the high-tech sector, in Ottawa. But he became so frustrated with CBC Radio 2 that he started his own blog: “CBC Radio 2 and Me,” to document his correspondence with CBC managers. “The CBC is a corporation that is completely opaque,” he charges. “You have to rely on them to tell the public if what they’re doing is successful. And Radio 2 management doesn’t seem to encourage people to make comments.”

It may be that the most enthusiastic (or, at least, the most determined) supporters of the changes to Radio 2 are the people who are making the changes. These may be found within the CBC’s managerial ranks – but they are not, generally, the announcers, producers and technicians for Radio 2’s programs. Unfortunately, the people who actually put the shows together are not very happy these days. They often refuse to publicly express their views on the subject of Radio 2, fearing this would endanger their careers. Some are voting with their feet, choosing to accept early retirement packages. One classical programmer, who cautiously agreed to talk to me (anonymously and off site), was dismissive of the managers who are behind the plans to overhaul Radio 2: “If these people didn’t change things, they wouldn’t have jobs.”

However, one of the managers behind the changes, Mark Steinmetz, agrees to talk about programming – although I suspect there are things he’d rather do. Indeed, it soon becomes apparent that he’s getting a little tired of defending Radio 2’s policies. “People say we’re intransigent because we’re not not changing,” he says with a touch of exasperation. “But we’ve talked to hundreds of stakeholders.”

According to statistics, Steinmetz says, only a small minority of Canadians – between 3 and 4 percent – tune in to Radio 2 in a typical week. As well, he cites research that indicates the aging Radio 2 audience is not being replaced by younger listeners. “We want to see a sustainable audience,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with older listeners, but what’s not good is that there’s no audience coming in behind them.” He also explains that audience-share varies considerably from one region of Canada to another. “Radio 2 has a much higher share in British Columbia or Ottawa than in Newfoundland, where it barely registers at all.”

And he points to the Broadcast Act. “Our goal is to adhere to our mandate,” he states, “which is often flung in my face by people who don’t agree with the changes. Currently, we’re not using the public space to reflect the broad range of music-making in this country.”

Steinmetz flatly denies that it’s the CBC’s intention to entirely eliminate classical music from Radio 2, and he also denies that external pressure from irate listeners will sway the corporation in its programming decisions. And while he doesn’t deny the number of broadcast-hours devoted to classical music have been substantially reduced in the last two years, he doesn’t see this as the issue. “It’s not about tonnage,” he insists. “The future of classical music isn’t going to hinge on playing it all day. It’s about creating engaging programming.”

As for the CBC Orchestra, he says that the decision to disband it was difficult, and made for purely economic reasons: the money can be put to better use elsewhere. “We will be upping the commissioning budget for contemporary music,” he assures me. What Steinmetz would rather talk about are some of the innovations that will soon be available from the CBC: streamed music on the internet, allowing listeners to hear classical music, and other genres, whenever they want; and downloadable concerts available for a year after an event is recorded. (What he doesn’t say is that Canadians living in rural areas where high-speed internet is not available will find it hard to access these services.)

Meanwhile, those opposed to the reduction of classical music at the CBC continue to organize and express their concerns. The resistance movement is strongest on the West Coast, where the CBC Vancouver Orchestra has been based for 70 years. But there are vocal groups in other regions, and on May 24 another round of rallies was held in cities across the country. The movement has organized its own publicity campaign; and has called upon both the CRTC and the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage to examine the issue. The debate may heat up again in the autumn, when (or if) the third round of changes to Radio 2 is implemented – and as the CBC Vancouver Orchestra’s final concert, on November 16, draws nigh.

I said I would conclude with my own opinions, so here they are. First, I should explain that although I’ve written about classical music for the Globe and Mail and other publications from time to time, I don’t consider myself a “fundamentalist”: I’m glad to say that there are other kinds of music I enjoy and respect. Also, I don’t subscribe to the view that the only kind of music worthy of the name “contemporary” is contemporary classical music.

However, I fear that the CBC is making a grave error in trying to mix such a wide array of musical styles and genres on a single radio network. Most radio listeners want the kind of music they want when they want it: when they want country music, they tune to a country station; when they want classical, they tune to a classical station. Private broadcasters understand how well-defined people’s musical tastes can be: a commercial radio station will generally stay within a clear, narrowly defined aesthetic, in order to carve out a distinctive voice in the marketplace. Steinmetz told me that “people are tired formatted radio.” But if he is wrong, Radio 2 could end up in a bad way: losing the loyal audience it has built up over the years, while failing to attract new listeners.

While I’m concerned about the reduction of classical music on Radio 2, I’m also disturbed by some of the other cuts to classical music at the CBC. The elimination of the national competitions for young performers and young composers is a blow to classical music in Canada – and it’s not yet clear how they will be effectively replaced. Without new releases from CBC Records, Canada’s classical musicians will lose a prestigious outlet for their talents. And the disbanding of the CBC Vancouver Orchestra will silence an excellent and unique ensemble that costs each Canadian a few pennies per year.

However, this isn’t just about a radio network or an orchestra – it’s also about the position of classical music in our society. Of late, of this once-honoured musical art has been losing ground in the forum of public perception. Newspapers have reduced coverage of classical music. Record stores that sell classical CDs are rare and getting rarer. Music education has been cut back in many schools. The art form is certainly not dying (on the contrary, there are many signs of vitality), but its “presence” is being eroded. Classical-music enthusiasts have been feeling marginalized for some time – and this probably helps to explain why the changes at Radio 2 have become such a sore point. The debate over the CBC’s policies is a struggle to determine if classical music can retain a place in Canada’s mainstream culture, or whether it will be relegated to the status of a “niche interest.”

And there’s even more at stake. In Canada, our governments offer a wide range of services – so wide that it would be impossible for any individual citizen to make use of all of them. This approach to providing services is founded on a very Canadian de-facto social contract: “If it’s not for you, it’s for someone else.” However, the changes to Radio 2 are ideologically grounded on the belief that all government-funded services should somehow be for everyone – and not just available to all, but to the taste of all. What else might we measure by this majoritarian yardstick? How many Canadians make use of public libraries, amateur sports programs, or national parks? Does the art hanging in the National Gallery reflect the full diversity of artistic expression in Canada? How does the Coast Guard benefit the people of Alberta and Saskatchewan?

And what about the CBC’s Radio 3 service, available on the internet and on Sirius? It plays “alt-pop” (alternative popular music) and “indie-rock” (independent rock music), and it’s not very diverse. Perhaps the Canadian singer-songwriters who the CBC’s managers claim are unduly neglected would find a happier home here, rather than shoehorned in with classical music on Radio 2. (Until recently, the CBC aspired to make Radio 3 into a full-fledged on-air network, but these plans were dropped due to lack of funding.)

Canada’s classical music community has often proven itself determined and resilient. Our orchestras struggle to survive – and, against all odds, they do. It took more than thirty years of lobbying for Toronto to get a proper opera house, but now it is built. Every summer a new chamber-music festival springs up somewhere. And our music faculties and conservatories continue to attract talented and enthusiastic students of classical music.

The CBC likes to give the impression that resistance is futile – that China will free Tibet before the corporation’s plans will be even slightly altered. But the decisions of the CBC’s managers are not carved in stone. Although they may chose to blithely overlook thousands of names on Facebook, they would find the concerns of elected officials much harder to ignore. (Despite the corporation’s “arm’s length” relationship with the federal government, the CBC knows where its bread is buttered.) To succeed, the resistance movement needs political support.

With intelligent, strategic persistence, and some allies in high places, it may still be possible for the CBC’s policies to be changed. However, if Canadians who care about classical music fail to speak up at this time, then perhaps they deserve to be marginalized.

© Copyright Colin Eatock 2008