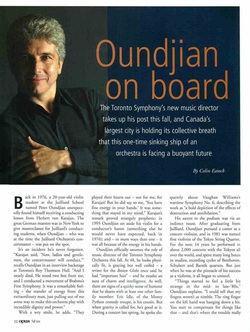

Oundjian on Board

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2004 issue of Opus magazine.

by Colin Eatock

Back in 1976, a 20-year-old violin student at the Juilliard School named Peter Oundjian unexpectedly found himself receiving a conducting lesson from Herbert von Karajan. The great maestro was in New York to give masterclasses for Juilliard’s conducting students, when Oundjian – who was at the time the Juilliard Orchestra’s concertmaster – was put on the spot.

It’s an incident that he’s never forgotten. “Karajan said, ‘Now, ladies and gentlemen, the concertmaster will conduct,’” recalls Oundjian in an interview at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall. “And I nearly died. He stood two feet from me, and I conducted a movement of Brahms’ First Symphony. It was a remarkable feeling – the transfer of energy from this extraordinary man, just pulling out of me some way to make this orchestra play with incredible dignity and power.”

With a wry smile, he adds, “They played their hearts out – not for me, for Karajan! But he did say to me, ‘You have fine energy in your hands.’ It was something that stayed in my mind.” Karajan’s remark proved strangely prophetic: in 1995 Oundjian set aside his violin for a conductor’s baton (something else he would never have expected, back in 1976); and – in more ways than one – it was all because of the energy in his hands.

Oundjian officially assumes the role of Music Director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra this fall. At 48, he looks physically fit, is graying but well coifed – a writer for the Boston Globe once said he had “important hair” – and he exudes an aura of charm and intelligence. As well, there are signs of a quirky sense of humour that he shares with at least one other family member: Eric Idle, of the Monty Python comedy troupe, is his cousin. But when gravity is called for, he’s good at it. During a concert this spring, he spoke eloquently about Vaughan Williams’ wartime Symphony No. 6, describing the work as “a bold depiction of the effects of destruction and annihilation.”

His ascent to the podium was via an indirect route. After graduating from Juilliard, Oundjian pursued a career as a concert artist, and in 1981 was named first violinist of the Tokyo String Quartet. For the next 14 years he performed in about 2,000 concerts with the Tokyos all over the world, and spent many long hours in studios, recording cycles of Beethoven, Schubert and Bartók quartets. But just when he was at pinnacle of his success as a violinist, it all began to unravel.

“Things started to feel a little bit strange in the mid- to late 80s,” Oundjian explains. “I could tell that my fingers weren’t as nimble. The ring finger on the left hand was hanging down a bit. You start to compensate for things like that – and that’s where the trouble really starts. You start making your muscles do the opposite of what they should: when you want to put a finger down, you have to lift it up first. By 1993 it had started to cause serious problems.”

His problem was focal dystonia, a disorder that interferes with the brain’s ability to communicate with the hand. It’s by no means unknown amongst musicians – the pianist Leon Fleisher has struggled with it for decades – and for many it is essentially incurable. “It’s hard enough to play the violin when you’ve got 100 percent facility, but when you’ve got a handicap, why bother?” Oundjian asks rhetorically. “There were so many movements that I just couldn’t play, and I didn’t really know where my fingers were going to go. For me, it was time to find something else to do.”

Faced with the kind of career meltdown would have sent many a musician spiraling into oblivion, Oundjian formulated a plan. In December 1994 he privately told his colleagues in the Tokyo Quartet that he would leave the group in May. He also contacted his friend André Previn, director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and also of the Caramoor Festival in New York State, and told him he was thinking of pursuing a musical interest that had been in the back of his mind for years.

“André Previn was extremely generous and kind,” says Oundjian, looking back on this time of transition. “He invited me to his house to talk about conducting. By the end of that meeting I felt incredibly inspired. And he invited me to lead the Orchestra of St. Luke’s at the opening night of Caramoor’s 50th-anniversary season.” The musical world lost a violinist but gained a conductor.

There are basically two kinds of conductors: those who decide at a young age they want to conduct and who focus their studies in that direction; and those who take up the baton later in life, often after achieving success as instrumentalists. Oundjian falls into the latter category – and that is, in his opinion, an advantage. “I played 300 or 400 performances of Beethoven’s late quartets. And so if I’m conducting Beethoven’s Ninth, I think I’m very lucky to have a feeling of what was going on in that man’s soul and that man’s mind, through playing the quartets.”

But he still had a lot to learn, so in the winter of 1995 he began to take conducting lessons from Previn and others. He also found a respected New York agent who was willing to take a chance on him – and within three years of his Caramoor Festival debut he was named Artistic Advisor and Principal Conductor to the festival (a title he still holds) and also Music Director of the Nieuw Sinfonietta Amsterdam (a position he relinquished last year). He’s also appeared in such European cities as London, Zurich, Frankfurt, and Monte Carlo; but he’s been busiest in North America, where he has guest conducted the orchestras of Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, San Francisco, Cincinnati and Salt Lake City, amongst others. Last year he was appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Colorado Symphony, in Denver.

And then there’s Toronto. Oundjian first appeared as a violin soloist with the TSO in 1981, and as a guest conductor in 1998. But his connection to the city goes back much further than that: he was born in Toronto in 1955, into a family of Armenian, English and French ancestry who were in the carpet business. However, just five years later his parents packed up their rugs and children and moved to the UK. Oundjian grew up in Surrey, where he acquired the soft accent that graces his speech.

Understandably, his childhood memories of Toronto are a little sketchy – but he nevertheless regards his appointment as the first locally born TSO music director since Sir Earnest MacMillan as a kind of homecoming. And, like anyone else who has followed the ups and downs of the TSO’s fortunes in the last few years, he’s well aware that his new job will be a challenge. “When I heard this orchestra was in so much trouble,” he states, “it broke my heart, because I love this city, and I couldn’t believe that this amazing city couldn’t sustain a great orchestra. I just couldn’t believe that.”

The “trouble” he speaks of was the near bankruptcy of the TSO in 2001. At the time, the orchestra had no conductor, no manager, no cash – and speculation was rife that it also had no future. It was hardly an auspicious time for the organization to be looking for a new music director.

“Quite honestly,” Oundjian points out, “why would a European conductor who’s got many choices and possibilities be troubled with a city that is obviously having a dysfunctional relationship with its orchestra? But for a guy who’s born here, and who believes in the city, it can be a calling. Something about it just told me it was something I should do – that I could make a difference.” His appointment, announced on January 16, 2003, had all the markings of a match made in heaven: the TSO needed a new conductor who could revive the orchestra’s prospects, and Oundjian, after years of guest conducting, needed an orchestra to call his own.

The wheels of the classical music world turn slowly, and so it has taken almost two years to fully install Oundjian in his new job. However, in the last couple of seasons he’s made increasingly frequent guest appearances with the TSO. And he’s received some favourable notices from the local critics: the Globe and Mail predicted that he “has a good chance of a big conducting career”; and the Toronto Star declared him “a conductor who brings with him both a fellow player’s credentials and a leader’s instincts.”

But it’s also been noted that he has not, as yet, shown any sign of moving to Toronto. Although he has a flat in town, his real home is in Weston, Connecticut, where he lives with his wife and two children. This is an issue that goes beyond mere window-dressing: these days a music director must also be an administrator, a fundraiser and a publicist – “someone who takes a real interest in the community,” as TSO President and CEO Andrew Shaw put it, when the orchestra was maestro-shopping. However, if Oundjian prefers to get his hair cut in New England, at least that’s not as far as the last conductor went for a trim: Jukka-Pekka Saraste’s barber was in Finland.

When not in Toronto, Oundjian will devote about a dozen weeks a year to guest appearances. And as he conducts his way around the USA, he is increasingly seen as a hot property. Last year a critic in St. Louis expressed regret that Toronto had snapped him up before that city’s leaderless orchestra could. And another music writer recently mentioned him as a prospective successor to Mariss Jansons, who recently stepped down from the podium of the Pittsburgh Symphony. But Oundjian makes it clear that he intends to stay with the TSO for some time. “I wouldn’t see the town of my birth, and the place to which I prefer to give my commitment, as a stepping-stone to anything,” he insists. “That’s not the way I look at it.”

So what, exactly, does he plan to accomplish in Toronto? Oundjian underscores several ways in which he hopes to enhance the TSO’s stature in the world. “It’s important that we have the opportunity to make some recordings, and that the public should have the opportunity to hear recordings of the TSO. It’s also important that the TSO go on tour and be heard all over the world.”

As for repertoire, he favours a cautious approach. “We have to be careful about programming because we’re in a business, and we have to balance the budget, otherwise people will lose faith in us. Part of being fiscally responsible is to produce programs that are innovative but inspire people to come out to the concert. You can’t get too esoteric.”

He continues: “The standard repertoire has been done many times, but audiences deserve to be nourished by that repertoire. To say we’ve had enough of Brahms’ symphonies is ridiculous – there’s something in that music that no other music has. So I want people to be able to hear at least one Brahms symphony every year. But there are many great works from the 20th century that have not been played often. I’m thinking of works by Martinu, Vaughan Williams, Nielsen, Honegger – and we do certain pieces by Stravinsky, but not others. We’re also looking for interesting Canadian voices.”

In his first season as the TSO’s Music Director, he’ll be conducting a lot of what he calls his “party pieces” – favourite works that he knows well. Beethoven is well represented: Oundjian will lead performances of the Third and Seventh symphonies, the “Emperor” Concerto with pianist Richard Goode, the overture to Fidelio and his own arrangement of Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 131. As well, he’s programmed a mini-festival to celebrate the 249th birthday of Mozart in January; and a “New Creations” festival in the spring, featuring contemporary works. (Among the living composers performed will be Canada’s R. Murray Schafer, who for the last decade has been boycotting the TSO, due to what he feels is a lack of support for Canadian music from the orchestra. It looks like the boycott is over.)

Since the TSO’s near-death experience three years ago, the orchestra’s fortunes have been on an upswing. Extensive work on Roy Thomson Hall resulted in substantial improvement to the Toronto auditorium’s acoustics. The orchestra’s finances have been stabilized, and subscriptions have increased. So Oundjian has good cause to be bullish about the TSO – he’s clearly enthusiastic about his new job, and he comes equipped with well-considered ideas about his role as music director.

“The Toronto Symphony is an orchestra of extraordinary skill,” he states with pride. “But to stay fresh as an ensemble is an ongoing endeavour. It’s not just maintenance – it’s not that simple, or neutral. This is an activity that requires constant nourishment and inspiration. We have to have an environment in which we really want to make great music every night. And from that, everything else comes. When the energy is positive, then the extraordinary music-making will be there – because the talent is already there.”

© Colin Eatock 2004

by Colin Eatock

Back in 1976, a 20-year-old violin student at the Juilliard School named Peter Oundjian unexpectedly found himself receiving a conducting lesson from Herbert von Karajan. The great maestro was in New York to give masterclasses for Juilliard’s conducting students, when Oundjian – who was at the time the Juilliard Orchestra’s concertmaster – was put on the spot.

It’s an incident that he’s never forgotten. “Karajan said, ‘Now, ladies and gentlemen, the concertmaster will conduct,’” recalls Oundjian in an interview at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall. “And I nearly died. He stood two feet from me, and I conducted a movement of Brahms’ First Symphony. It was a remarkable feeling – the transfer of energy from this extraordinary man, just pulling out of me some way to make this orchestra play with incredible dignity and power.”

With a wry smile, he adds, “They played their hearts out – not for me, for Karajan! But he did say to me, ‘You have fine energy in your hands.’ It was something that stayed in my mind.” Karajan’s remark proved strangely prophetic: in 1995 Oundjian set aside his violin for a conductor’s baton (something else he would never have expected, back in 1976); and – in more ways than one – it was all because of the energy in his hands.

Oundjian officially assumes the role of Music Director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra this fall. At 48, he looks physically fit, is graying but well coifed – a writer for the Boston Globe once said he had “important hair” – and he exudes an aura of charm and intelligence. As well, there are signs of a quirky sense of humour that he shares with at least one other family member: Eric Idle, of the Monty Python comedy troupe, is his cousin. But when gravity is called for, he’s good at it. During a concert this spring, he spoke eloquently about Vaughan Williams’ wartime Symphony No. 6, describing the work as “a bold depiction of the effects of destruction and annihilation.”

His ascent to the podium was via an indirect route. After graduating from Juilliard, Oundjian pursued a career as a concert artist, and in 1981 was named first violinist of the Tokyo String Quartet. For the next 14 years he performed in about 2,000 concerts with the Tokyos all over the world, and spent many long hours in studios, recording cycles of Beethoven, Schubert and Bartók quartets. But just when he was at pinnacle of his success as a violinist, it all began to unravel.

“Things started to feel a little bit strange in the mid- to late 80s,” Oundjian explains. “I could tell that my fingers weren’t as nimble. The ring finger on the left hand was hanging down a bit. You start to compensate for things like that – and that’s where the trouble really starts. You start making your muscles do the opposite of what they should: when you want to put a finger down, you have to lift it up first. By 1993 it had started to cause serious problems.”

His problem was focal dystonia, a disorder that interferes with the brain’s ability to communicate with the hand. It’s by no means unknown amongst musicians – the pianist Leon Fleisher has struggled with it for decades – and for many it is essentially incurable. “It’s hard enough to play the violin when you’ve got 100 percent facility, but when you’ve got a handicap, why bother?” Oundjian asks rhetorically. “There were so many movements that I just couldn’t play, and I didn’t really know where my fingers were going to go. For me, it was time to find something else to do.”

Faced with the kind of career meltdown would have sent many a musician spiraling into oblivion, Oundjian formulated a plan. In December 1994 he privately told his colleagues in the Tokyo Quartet that he would leave the group in May. He also contacted his friend André Previn, director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and also of the Caramoor Festival in New York State, and told him he was thinking of pursuing a musical interest that had been in the back of his mind for years.

“André Previn was extremely generous and kind,” says Oundjian, looking back on this time of transition. “He invited me to his house to talk about conducting. By the end of that meeting I felt incredibly inspired. And he invited me to lead the Orchestra of St. Luke’s at the opening night of Caramoor’s 50th-anniversary season.” The musical world lost a violinist but gained a conductor.

There are basically two kinds of conductors: those who decide at a young age they want to conduct and who focus their studies in that direction; and those who take up the baton later in life, often after achieving success as instrumentalists. Oundjian falls into the latter category – and that is, in his opinion, an advantage. “I played 300 or 400 performances of Beethoven’s late quartets. And so if I’m conducting Beethoven’s Ninth, I think I’m very lucky to have a feeling of what was going on in that man’s soul and that man’s mind, through playing the quartets.”

But he still had a lot to learn, so in the winter of 1995 he began to take conducting lessons from Previn and others. He also found a respected New York agent who was willing to take a chance on him – and within three years of his Caramoor Festival debut he was named Artistic Advisor and Principal Conductor to the festival (a title he still holds) and also Music Director of the Nieuw Sinfonietta Amsterdam (a position he relinquished last year). He’s also appeared in such European cities as London, Zurich, Frankfurt, and Monte Carlo; but he’s been busiest in North America, where he has guest conducted the orchestras of Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, San Francisco, Cincinnati and Salt Lake City, amongst others. Last year he was appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Colorado Symphony, in Denver.

And then there’s Toronto. Oundjian first appeared as a violin soloist with the TSO in 1981, and as a guest conductor in 1998. But his connection to the city goes back much further than that: he was born in Toronto in 1955, into a family of Armenian, English and French ancestry who were in the carpet business. However, just five years later his parents packed up their rugs and children and moved to the UK. Oundjian grew up in Surrey, where he acquired the soft accent that graces his speech.

Understandably, his childhood memories of Toronto are a little sketchy – but he nevertheless regards his appointment as the first locally born TSO music director since Sir Earnest MacMillan as a kind of homecoming. And, like anyone else who has followed the ups and downs of the TSO’s fortunes in the last few years, he’s well aware that his new job will be a challenge. “When I heard this orchestra was in so much trouble,” he states, “it broke my heart, because I love this city, and I couldn’t believe that this amazing city couldn’t sustain a great orchestra. I just couldn’t believe that.”

The “trouble” he speaks of was the near bankruptcy of the TSO in 2001. At the time, the orchestra had no conductor, no manager, no cash – and speculation was rife that it also had no future. It was hardly an auspicious time for the organization to be looking for a new music director.

“Quite honestly,” Oundjian points out, “why would a European conductor who’s got many choices and possibilities be troubled with a city that is obviously having a dysfunctional relationship with its orchestra? But for a guy who’s born here, and who believes in the city, it can be a calling. Something about it just told me it was something I should do – that I could make a difference.” His appointment, announced on January 16, 2003, had all the markings of a match made in heaven: the TSO needed a new conductor who could revive the orchestra’s prospects, and Oundjian, after years of guest conducting, needed an orchestra to call his own.

The wheels of the classical music world turn slowly, and so it has taken almost two years to fully install Oundjian in his new job. However, in the last couple of seasons he’s made increasingly frequent guest appearances with the TSO. And he’s received some favourable notices from the local critics: the Globe and Mail predicted that he “has a good chance of a big conducting career”; and the Toronto Star declared him “a conductor who brings with him both a fellow player’s credentials and a leader’s instincts.”

But it’s also been noted that he has not, as yet, shown any sign of moving to Toronto. Although he has a flat in town, his real home is in Weston, Connecticut, where he lives with his wife and two children. This is an issue that goes beyond mere window-dressing: these days a music director must also be an administrator, a fundraiser and a publicist – “someone who takes a real interest in the community,” as TSO President and CEO Andrew Shaw put it, when the orchestra was maestro-shopping. However, if Oundjian prefers to get his hair cut in New England, at least that’s not as far as the last conductor went for a trim: Jukka-Pekka Saraste’s barber was in Finland.

When not in Toronto, Oundjian will devote about a dozen weeks a year to guest appearances. And as he conducts his way around the USA, he is increasingly seen as a hot property. Last year a critic in St. Louis expressed regret that Toronto had snapped him up before that city’s leaderless orchestra could. And another music writer recently mentioned him as a prospective successor to Mariss Jansons, who recently stepped down from the podium of the Pittsburgh Symphony. But Oundjian makes it clear that he intends to stay with the TSO for some time. “I wouldn’t see the town of my birth, and the place to which I prefer to give my commitment, as a stepping-stone to anything,” he insists. “That’s not the way I look at it.”

So what, exactly, does he plan to accomplish in Toronto? Oundjian underscores several ways in which he hopes to enhance the TSO’s stature in the world. “It’s important that we have the opportunity to make some recordings, and that the public should have the opportunity to hear recordings of the TSO. It’s also important that the TSO go on tour and be heard all over the world.”

As for repertoire, he favours a cautious approach. “We have to be careful about programming because we’re in a business, and we have to balance the budget, otherwise people will lose faith in us. Part of being fiscally responsible is to produce programs that are innovative but inspire people to come out to the concert. You can’t get too esoteric.”

He continues: “The standard repertoire has been done many times, but audiences deserve to be nourished by that repertoire. To say we’ve had enough of Brahms’ symphonies is ridiculous – there’s something in that music that no other music has. So I want people to be able to hear at least one Brahms symphony every year. But there are many great works from the 20th century that have not been played often. I’m thinking of works by Martinu, Vaughan Williams, Nielsen, Honegger – and we do certain pieces by Stravinsky, but not others. We’re also looking for interesting Canadian voices.”

In his first season as the TSO’s Music Director, he’ll be conducting a lot of what he calls his “party pieces” – favourite works that he knows well. Beethoven is well represented: Oundjian will lead performances of the Third and Seventh symphonies, the “Emperor” Concerto with pianist Richard Goode, the overture to Fidelio and his own arrangement of Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 131. As well, he’s programmed a mini-festival to celebrate the 249th birthday of Mozart in January; and a “New Creations” festival in the spring, featuring contemporary works. (Among the living composers performed will be Canada’s R. Murray Schafer, who for the last decade has been boycotting the TSO, due to what he feels is a lack of support for Canadian music from the orchestra. It looks like the boycott is over.)

Since the TSO’s near-death experience three years ago, the orchestra’s fortunes have been on an upswing. Extensive work on Roy Thomson Hall resulted in substantial improvement to the Toronto auditorium’s acoustics. The orchestra’s finances have been stabilized, and subscriptions have increased. So Oundjian has good cause to be bullish about the TSO – he’s clearly enthusiastic about his new job, and he comes equipped with well-considered ideas about his role as music director.

“The Toronto Symphony is an orchestra of extraordinary skill,” he states with pride. “But to stay fresh as an ensemble is an ongoing endeavour. It’s not just maintenance – it’s not that simple, or neutral. This is an activity that requires constant nourishment and inspiration. We have to have an environment in which we really want to make great music every night. And from that, everything else comes. When the energy is positive, then the extraordinary music-making will be there – because the talent is already there.”

© Colin Eatock 2004