Six Canadian Composers You Should Know

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2011 issue of Queen’s Quarterly, a journal published by Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada.

by Colin Eatock

Over the years, Canadian “classical” music has acquired an unfortunate reputation. It’s boring. It’s ugly. It’s incomprehensible. Alas, there’s some truth in this – and I’m certainly not writing in defense of all Canadian music. Rather, what I want to do here is undertake a little haystack sifting, to extract a few precious needles: Canadian composers who have succeeded in creating beautiful, fascinating and moving works. These are composers who deserve to be known, heard and admired by audiences.

I’ve chosen six composers. They are men and women, Anglophone and Francophone, and they represent a wide range of styles and aesthetic positions. However, they all have one thing in common: they are deceased. While dead composers often fall into obscurity (and that is often as it should be), I’m hoping that my selected six will flourish in their musical after-lives. Canadians should know that this country is slowly but surely developing a rich and valuable classical music heritage. And because they’ve all been recorded on CDs, their music can be heard anywhere, anytime, not just in rare live performances.

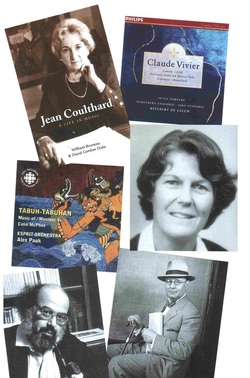

The composers (in alphabetical order) are Jean Coulthard, Jacques Hétu, Colin McPhee, Ann Southam, Claude Vivier and Healey Willan. Some readers may notice the conspicuous absence of several important Canadian composers who enjoyed prominent and productive careers. But an “important” composer isn’t always a good one, and my list is entirely subjective. I’m indulging my own personal tastes – but I’m also trying to be helpful. If it’s better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness, let’s light half a dozen candles.

Jean Coulthard was born in Vancouver in 1908, and passed away there in 2000. For two years she studied at London’s Royal College of Music, where her instructors included Ralph Vaughan Williams. The experience left an English stamp on her music: a sense of propriety and poise, and a penchant for a kind of loose tonality that’s often called “modal.” In terms of her musical influences, Bartók (with whom she studied briefly) was about as strident as she got – and for this reason, she didn’t really fit in with some of her modernist colleagues at the University of British Columbia.

Yet if she was regarded by some as hopelessly conservative, she wasn’t about to deviate from her core values. “I’ve never made a direct effort to change my style,” she told a journalist in 1989. “I’ve always tried to write what I call ‘naturally,’ in the natural way I feel. I think one’s best works come out that way.”

To be sure, her music lacks the aggressiveness of modernism, but there’s an underlying strength in her works, which comes from a thorough knowledge of classical form and a firm sense of organic inevitability. Melodies are well shaped and balanced, crescendos are carefully prepared and built up: there’s nothing about her music that seems out of place. This is craft raised to a level where it becomes enfolded in unconscious expression.

There are a few CDs currently available that are entirely devoted to the works of Coulthard. One can be found in Ovation Vol. 1, a five-disc box of music by Canadian composers issued by CBC Records (PSCD 2026-5), back in the days when the CBC had a record label. There are several orchestral compositions, including the Introduction and Three Folksongs and Quebec May (with choir): both lush and lyrical works, with pastoral Appalachian Spring-like touches. (Aaron Copland was yet another of her teachers.) A special treat is Spring Rhapsody, a song-cycle composed for the late Maureen Forrester, with piano. And the disc also includes a lovely solo harp piece, Of Fields and Forests.

As well, there’s a two-disc set of Coulthard that’s been issued by the Canadian Music Centre, on the Centrediscs label (Canadian Composers Portraits: Jean Coulthard, CMCCD 8202). It gives a slightly different impression of this composer. Her Piano Concerto is surprisingly bombastic in its outer movements: grandly romantic, it sounds like Rachmaninoff’s stepchild. Sketches From the Western Woods, for solo piano, is not as innocently bucolic as some of her other nature-themed works. And in her Twelve Essays on a Cantabile Theme, for string octet, she steps outside her romantic comfort-zone and explores new stylistic territories. This may not be her most “natural” piece, but it’s impressive, nonetheless.

Much as Coulthard was oriented towards England, Jacques Hétu (who was born in Trois-Rivières in 1938 and who passed away last year) looked to France. Winning the Quebec Government’s Prix d’Europe in 1961 allowed him to spend two years in Paris studying with the renowned French composers Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux, and the experience left a Gallic mark on his music. Upon his return to Canada, Hétu became a university professor, teaching first in Quebec City and later in Montreal.

In his early works he embraced modernist trends – yet always on his own terms. “I am first and foremost a melodist,” he asserted. “Melody is the most important element of my style.” By the 1990s he described his harmonic language as “near the tonal system, but not quite in it.” Indeed, a kind of elusive flexibility was his trademark: while there’s often no fixed tonal centre that can be nailed to the wall, the strident dissonances of Stockhausen, Boulez, et al. are rarely heard. Add to that a narrative structure that’s based on established Western models, and you have a modernist whose music is both clear and dramatically sure-footed. Summarizing his style, Hétu once remarked, “My structures are classical, my expression is romantic and my vocabulary is contemporary.”

Hétu also has a disc in the Ovation Vol. 1 set. First on the CD is his Symphony No. 3 (one of five symphonies he composed). It’s a slender work, just over 18 minutes in length, but it punches above its weight, with a sinewy, brooding, quality suggestive of Shostakovich. Two concertos follow, for guitar and for trumpet. Both are delicately balanced pieces, more intimate and less ostentatious than concertos often are. And the last piece on the disc, a short orchestral work called Antinomie, is a study in dramatic contrasts: here, his palette of colours ranges from a lone oboe to percussive Rite of Spring rhythms for the whole orchestra.

The CBC also released a compact disc consisting entirely of Hétu’s concertos (SMCD 5228). There are three woodwind concertos – for flute, clarinet and bassoon – and they’re all good pieces. However, the Piano Concerto No. 2 is outstanding: an intense and riveting work from start to finish. Anyone who likes Prokofiev’s piano concertos will surely like this music. As well, Hétu is featured on one of the Canadian Music Centre’s “Composer Portrait” releases (CMCCD 8302).

Like many Canadian composers in the 20th century, Colin McPhee also looked beyond the borders of this country for musical inspiration. Born in Montreal in 1900, and raised in Toronto, the prodigiously talented McPhee studied classical music in Philadelphia and Paris, and then spent some time in New York City. But a recording of an Indonesian gamelan – an ensemble of bronze percussion instruments – was an epiphany. “The clear metallic sounds,” he wrote, “were like the stirring of a thousand bells, delicate, confused, with a sensuous charm, a mystery that was quite overpowering.” In 1931 he packed his bags and went to Bali, where he spent most of the next decade. There, he undertook a groundbreaking ethnological study of the local music, and the distinctive timbres of Indonesian music found their way into his own compositions.

There exists only one CD entirely devoted to McPhee’s music, a CBC release (SMCD 5181), and it’s quite good. The disc’s name is the same as McPhee’s most famous composition: Tabuh-Tabuhan, a three-movement symphonic work for orchestra. For this piece, the composer created a “virtual gamelan” – two pianos, plus xylophone, glockenspiel, marimba and other percussion instruments – and built the rest of the orchestra up around this nucleus. The result is an intricately patterned East-meets-West sonority: something like Steve Reich and Philip Glass’s minimalism, only four decades earlier.

My own favourite McPhee work on this disc is his Symphony No. 2, a work that’s formally European in structure, but audibly Indonesian in many ways. Here, McPhee makes use of Indonesian scales, colours and melodic gestures, often with a formal, aristocratic sense of restraint. Also on the disc is McPhee’s Concerto for Wind Instruments, a well-crafted work, with some beautifully exotic flute and oboe melodies in the second movement. As well, there’s an intense one-movement composition called Transitions, and a charming little piece called Nocturne, for chamber orchestra.

When the outbreak of World War II forced McPhee to leave Indonesia, he returned not to Canada but to the United States, where he never really readjusted to professional life in a Western society. He died in Los Angeles in 1964. In addition to his music, McPhee is remembered as the author of a delightfully readable memoir called A House in Bali.

If McPhee anticipated minimalism, Ann Southam immersed herself in it – but not before she passed through several other stylistic stages. Born in Winnipeg in 1937 (into the Southam newspaper family), she spent almost her entire life in Toronto, passing away there last year. Conspicuously, she did not go abroad for her musical education, but studied at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music, where she later taught. Her earliest works were romantic in nature, but in the 1960s she took an interest in Schoenbergian serialism and electronic music, creating pre-recorded electroacoustic dance pieces for Toronto Dance Theatre.

But today she’s best known for her minimalist works. In 1999, she recounted one of her first experiences of minimalism: hearing A Rainbow in Curved Air by the American composer Terry Riley. “This recording was tremendously sunny music, with tunes swirling over and over,” she recalled. “I loved the feel of it – like insects in the Fall grass, and as if the whole world was singing.”

Southam’s masterpiece is a 19-movement suite of piano pieces called Rivers that spans two CDs and is about two hours long. (It’s available on a set from Centrediscs: CMCCD 10505.) Rivers is, in fact, an intertwining of three separate sets of piano pieces. The largest (Set 3) is nine movements long and is the most “conventionally” minimalist: fast and flowing music made of kaleidoscopic patterns in a continual state of flux. Set 2 (eight movements) is tranquil and reflective; and Set 1 (two movements) is a cross between the styles of Sets 2 and 3. Assembled together, the movements of Rivers become a fluid continuum. Yet unlike some minimalists, Southam is neither obsessive nor oppressive: rather, her music is fresh, chromatically enriched and bursting with ideas.

Southam wrote a few pieces for string orchestra and chamber ensembles, and a good sampling of these works can be heard on Glass Houses, issued on the CBC’s Musica Viva label (MVCD 1124). But most of the time, Southam was loyal to the piano as her artistic medium of choice – and as she declined to write for wind instruments or the human voice, big symphonies, choral works and operas were out of the question. Perhaps this held her back: for many years, she was a relatively obscure figure in Canadian music. It was only late in her life that she won substantial recognition in Canada and came to be known internationally. Today, her star seems to be on the rise.

Claude Vivier was born in 1948, to unknown parents somewhere in the Montreal area, and adopted into the Vivier family at the age of three. Education at a Catholic school was intended to prepare him for the priesthood – but his love of music won out, and he enrolled at the Conservatoire de musique du Québec in Montreal. Study in Holland and Germany followed, and also an extensive trip to Asia in 1977 (he travelled from Iran to Indonesia). Like a sponge, Vivier absorbed everything from European high-modernism to the ancient Eastern traditions and forged his own style: richly nuanced in texture, but almost devoid of counterpoint.

Vivier was undoubtedly endowed with a brilliant musical mind. Yet I include him on my list with a strong caveat: I certainly don’t admire all of his works, which run the gamut from arrestingly simple and beautiful to confused and garishly opaque. So although there are several Vivier CDs currently available, it’s hard to find one to recommend wholeheartedly.

Nevertheless, I’ve chosen the compact disc Claude Vivier (Philips 454231), because it contains what I think is his finest work: Lonely Child, for orchestra and soprano. The text is in Vivier’s own invented “language” – deliberately unintelligible, yet paradoxically expressive and poignant. It’s a stately, ritualistic, and eerily dramatic work, something like Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, only much stranger. Also on this disc is Zipangu: a breathtaking juxtaposition of cries and whispers for string orchestra. However, the two remaining works on this disc are, I think, problematic: his Bouchara is unyielding, and his Prologue pour un Marco Polo is intractably long.

Vivier taught for a couple of years at the University of Ottawa, but preferred to eke out a meagre living as a freelance composer. Often described as child-like, he could behave outrageously in public, and liked to live dangerously – which may well have contributed to his murder in Paris in 1983, at the age of 34. Yet as an artist he was serious and high-minded, and once expressed the hope that his work would have “a human meaning that no music has been able to achieve until now.” It’s hard to know if he was profoundly happy or profoundly sad. Perhaps he was both.

We come at last to Healey Willan: the only composer on my list who was not Canadian by birth, although he spent most of his life in this country. He was born in England, just outside London, in 1880, and established himself in Toronto in 1913, where he passed away in 1968. An accomplished organist and composer, he headed the Theory Department at the Toronto (now Royal) Conservatory of Music, and later taught at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music. However, his most musically significant appointment was at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in 1921, where he conducted and composed for superb choral forces. He was prolific, penning over 700 works in his lifetime, ranging from small motets to full-scale symphonies.

Willan is well represented on several discs, which are mostly devoted to his choral and organ works. Choir and organ are combined on the CD In the Heavenly Kingdom (Naxos 8-557734); and his organ works alone can be heard on Healey Willan Organ Works (Naxos 8.557375). However, I’m most fond of a 1994 release (Virgin Classics 45109) that’s entirely given over to works for a-cappella choir. The disc also gives a good overview of his stylistic inclinations.

It’s often pointed out that Willan owed much to such 19th-century English composers as Parry, Stanford and Stainer, and this is certainly true. From the first track on the Virgin Classics disc, Immortal, Invisible, God only Wise, there’s a tranquil elegance to his style, and his part-writing is as smooth as silk. But two other prominent influences can be heard in the two short masses recorded here: Renaissance polyphony in his Missa Brevis No. 11; and Gregorian chant in his Missa Brevis No. 4. And what of modernism? Willan was cool to many trends in 20th-century music – but there are some adventurous harmonies in Who is She that Ascendeth?, and some juicy sonorities in Rise Up My Love.

While he was alive, Willan was known as “the Dean of Canadian Composers.” Yet towards the end of his long teaching career, he came to be regarded as a dinosaur, and he knew it. However, it didn’t seem to bother him much. “Music has been my chief delight,” he observed, “and if at any time I have been able to share that delight with others, I am content.”

I’m glad to say that none of my chosen composers has fallen into complete neglect. Their music is too good for that, and a small core of committed musicians is keeping their works alive. (Unfortunately, space constraints have prevented me from saying much about these performers. To make amends, I’ll mention two: Toronto’s Esprit Orchestra, which recorded the works of Colin McPhee; and the pianist Christina Petrowska-Quilico, who has done much to make Ann Southam’s music known.)

That’s all well and good – but these six composers should be household names in Canada, like Margaret Atwood or A.Y. Jackson. And while all listeners may not share my views about each and every piece I’ve mentioned, I guarantee there’s something here for everyone. Trust me – have I ever lied to you before?

© Colin Eatock 2011

by Colin Eatock

Over the years, Canadian “classical” music has acquired an unfortunate reputation. It’s boring. It’s ugly. It’s incomprehensible. Alas, there’s some truth in this – and I’m certainly not writing in defense of all Canadian music. Rather, what I want to do here is undertake a little haystack sifting, to extract a few precious needles: Canadian composers who have succeeded in creating beautiful, fascinating and moving works. These are composers who deserve to be known, heard and admired by audiences.

I’ve chosen six composers. They are men and women, Anglophone and Francophone, and they represent a wide range of styles and aesthetic positions. However, they all have one thing in common: they are deceased. While dead composers often fall into obscurity (and that is often as it should be), I’m hoping that my selected six will flourish in their musical after-lives. Canadians should know that this country is slowly but surely developing a rich and valuable classical music heritage. And because they’ve all been recorded on CDs, their music can be heard anywhere, anytime, not just in rare live performances.

The composers (in alphabetical order) are Jean Coulthard, Jacques Hétu, Colin McPhee, Ann Southam, Claude Vivier and Healey Willan. Some readers may notice the conspicuous absence of several important Canadian composers who enjoyed prominent and productive careers. But an “important” composer isn’t always a good one, and my list is entirely subjective. I’m indulging my own personal tastes – but I’m also trying to be helpful. If it’s better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness, let’s light half a dozen candles.

Jean Coulthard was born in Vancouver in 1908, and passed away there in 2000. For two years she studied at London’s Royal College of Music, where her instructors included Ralph Vaughan Williams. The experience left an English stamp on her music: a sense of propriety and poise, and a penchant for a kind of loose tonality that’s often called “modal.” In terms of her musical influences, Bartók (with whom she studied briefly) was about as strident as she got – and for this reason, she didn’t really fit in with some of her modernist colleagues at the University of British Columbia.

Yet if she was regarded by some as hopelessly conservative, she wasn’t about to deviate from her core values. “I’ve never made a direct effort to change my style,” she told a journalist in 1989. “I’ve always tried to write what I call ‘naturally,’ in the natural way I feel. I think one’s best works come out that way.”

To be sure, her music lacks the aggressiveness of modernism, but there’s an underlying strength in her works, which comes from a thorough knowledge of classical form and a firm sense of organic inevitability. Melodies are well shaped and balanced, crescendos are carefully prepared and built up: there’s nothing about her music that seems out of place. This is craft raised to a level where it becomes enfolded in unconscious expression.

There are a few CDs currently available that are entirely devoted to the works of Coulthard. One can be found in Ovation Vol. 1, a five-disc box of music by Canadian composers issued by CBC Records (PSCD 2026-5), back in the days when the CBC had a record label. There are several orchestral compositions, including the Introduction and Three Folksongs and Quebec May (with choir): both lush and lyrical works, with pastoral Appalachian Spring-like touches. (Aaron Copland was yet another of her teachers.) A special treat is Spring Rhapsody, a song-cycle composed for the late Maureen Forrester, with piano. And the disc also includes a lovely solo harp piece, Of Fields and Forests.

As well, there’s a two-disc set of Coulthard that’s been issued by the Canadian Music Centre, on the Centrediscs label (Canadian Composers Portraits: Jean Coulthard, CMCCD 8202). It gives a slightly different impression of this composer. Her Piano Concerto is surprisingly bombastic in its outer movements: grandly romantic, it sounds like Rachmaninoff’s stepchild. Sketches From the Western Woods, for solo piano, is not as innocently bucolic as some of her other nature-themed works. And in her Twelve Essays on a Cantabile Theme, for string octet, she steps outside her romantic comfort-zone and explores new stylistic territories. This may not be her most “natural” piece, but it’s impressive, nonetheless.

Much as Coulthard was oriented towards England, Jacques Hétu (who was born in Trois-Rivières in 1938 and who passed away last year) looked to France. Winning the Quebec Government’s Prix d’Europe in 1961 allowed him to spend two years in Paris studying with the renowned French composers Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux, and the experience left a Gallic mark on his music. Upon his return to Canada, Hétu became a university professor, teaching first in Quebec City and later in Montreal.

In his early works he embraced modernist trends – yet always on his own terms. “I am first and foremost a melodist,” he asserted. “Melody is the most important element of my style.” By the 1990s he described his harmonic language as “near the tonal system, but not quite in it.” Indeed, a kind of elusive flexibility was his trademark: while there’s often no fixed tonal centre that can be nailed to the wall, the strident dissonances of Stockhausen, Boulez, et al. are rarely heard. Add to that a narrative structure that’s based on established Western models, and you have a modernist whose music is both clear and dramatically sure-footed. Summarizing his style, Hétu once remarked, “My structures are classical, my expression is romantic and my vocabulary is contemporary.”

Hétu also has a disc in the Ovation Vol. 1 set. First on the CD is his Symphony No. 3 (one of five symphonies he composed). It’s a slender work, just over 18 minutes in length, but it punches above its weight, with a sinewy, brooding, quality suggestive of Shostakovich. Two concertos follow, for guitar and for trumpet. Both are delicately balanced pieces, more intimate and less ostentatious than concertos often are. And the last piece on the disc, a short orchestral work called Antinomie, is a study in dramatic contrasts: here, his palette of colours ranges from a lone oboe to percussive Rite of Spring rhythms for the whole orchestra.

The CBC also released a compact disc consisting entirely of Hétu’s concertos (SMCD 5228). There are three woodwind concertos – for flute, clarinet and bassoon – and they’re all good pieces. However, the Piano Concerto No. 2 is outstanding: an intense and riveting work from start to finish. Anyone who likes Prokofiev’s piano concertos will surely like this music. As well, Hétu is featured on one of the Canadian Music Centre’s “Composer Portrait” releases (CMCCD 8302).

Like many Canadian composers in the 20th century, Colin McPhee also looked beyond the borders of this country for musical inspiration. Born in Montreal in 1900, and raised in Toronto, the prodigiously talented McPhee studied classical music in Philadelphia and Paris, and then spent some time in New York City. But a recording of an Indonesian gamelan – an ensemble of bronze percussion instruments – was an epiphany. “The clear metallic sounds,” he wrote, “were like the stirring of a thousand bells, delicate, confused, with a sensuous charm, a mystery that was quite overpowering.” In 1931 he packed his bags and went to Bali, where he spent most of the next decade. There, he undertook a groundbreaking ethnological study of the local music, and the distinctive timbres of Indonesian music found their way into his own compositions.

There exists only one CD entirely devoted to McPhee’s music, a CBC release (SMCD 5181), and it’s quite good. The disc’s name is the same as McPhee’s most famous composition: Tabuh-Tabuhan, a three-movement symphonic work for orchestra. For this piece, the composer created a “virtual gamelan” – two pianos, plus xylophone, glockenspiel, marimba and other percussion instruments – and built the rest of the orchestra up around this nucleus. The result is an intricately patterned East-meets-West sonority: something like Steve Reich and Philip Glass’s minimalism, only four decades earlier.

My own favourite McPhee work on this disc is his Symphony No. 2, a work that’s formally European in structure, but audibly Indonesian in many ways. Here, McPhee makes use of Indonesian scales, colours and melodic gestures, often with a formal, aristocratic sense of restraint. Also on the disc is McPhee’s Concerto for Wind Instruments, a well-crafted work, with some beautifully exotic flute and oboe melodies in the second movement. As well, there’s an intense one-movement composition called Transitions, and a charming little piece called Nocturne, for chamber orchestra.

When the outbreak of World War II forced McPhee to leave Indonesia, he returned not to Canada but to the United States, where he never really readjusted to professional life in a Western society. He died in Los Angeles in 1964. In addition to his music, McPhee is remembered as the author of a delightfully readable memoir called A House in Bali.

If McPhee anticipated minimalism, Ann Southam immersed herself in it – but not before she passed through several other stylistic stages. Born in Winnipeg in 1937 (into the Southam newspaper family), she spent almost her entire life in Toronto, passing away there last year. Conspicuously, she did not go abroad for her musical education, but studied at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music, where she later taught. Her earliest works were romantic in nature, but in the 1960s she took an interest in Schoenbergian serialism and electronic music, creating pre-recorded electroacoustic dance pieces for Toronto Dance Theatre.

But today she’s best known for her minimalist works. In 1999, she recounted one of her first experiences of minimalism: hearing A Rainbow in Curved Air by the American composer Terry Riley. “This recording was tremendously sunny music, with tunes swirling over and over,” she recalled. “I loved the feel of it – like insects in the Fall grass, and as if the whole world was singing.”

Southam’s masterpiece is a 19-movement suite of piano pieces called Rivers that spans two CDs and is about two hours long. (It’s available on a set from Centrediscs: CMCCD 10505.) Rivers is, in fact, an intertwining of three separate sets of piano pieces. The largest (Set 3) is nine movements long and is the most “conventionally” minimalist: fast and flowing music made of kaleidoscopic patterns in a continual state of flux. Set 2 (eight movements) is tranquil and reflective; and Set 1 (two movements) is a cross between the styles of Sets 2 and 3. Assembled together, the movements of Rivers become a fluid continuum. Yet unlike some minimalists, Southam is neither obsessive nor oppressive: rather, her music is fresh, chromatically enriched and bursting with ideas.

Southam wrote a few pieces for string orchestra and chamber ensembles, and a good sampling of these works can be heard on Glass Houses, issued on the CBC’s Musica Viva label (MVCD 1124). But most of the time, Southam was loyal to the piano as her artistic medium of choice – and as she declined to write for wind instruments or the human voice, big symphonies, choral works and operas were out of the question. Perhaps this held her back: for many years, she was a relatively obscure figure in Canadian music. It was only late in her life that she won substantial recognition in Canada and came to be known internationally. Today, her star seems to be on the rise.

Claude Vivier was born in 1948, to unknown parents somewhere in the Montreal area, and adopted into the Vivier family at the age of three. Education at a Catholic school was intended to prepare him for the priesthood – but his love of music won out, and he enrolled at the Conservatoire de musique du Québec in Montreal. Study in Holland and Germany followed, and also an extensive trip to Asia in 1977 (he travelled from Iran to Indonesia). Like a sponge, Vivier absorbed everything from European high-modernism to the ancient Eastern traditions and forged his own style: richly nuanced in texture, but almost devoid of counterpoint.

Vivier was undoubtedly endowed with a brilliant musical mind. Yet I include him on my list with a strong caveat: I certainly don’t admire all of his works, which run the gamut from arrestingly simple and beautiful to confused and garishly opaque. So although there are several Vivier CDs currently available, it’s hard to find one to recommend wholeheartedly.

Nevertheless, I’ve chosen the compact disc Claude Vivier (Philips 454231), because it contains what I think is his finest work: Lonely Child, for orchestra and soprano. The text is in Vivier’s own invented “language” – deliberately unintelligible, yet paradoxically expressive and poignant. It’s a stately, ritualistic, and eerily dramatic work, something like Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, only much stranger. Also on this disc is Zipangu: a breathtaking juxtaposition of cries and whispers for string orchestra. However, the two remaining works on this disc are, I think, problematic: his Bouchara is unyielding, and his Prologue pour un Marco Polo is intractably long.

Vivier taught for a couple of years at the University of Ottawa, but preferred to eke out a meagre living as a freelance composer. Often described as child-like, he could behave outrageously in public, and liked to live dangerously – which may well have contributed to his murder in Paris in 1983, at the age of 34. Yet as an artist he was serious and high-minded, and once expressed the hope that his work would have “a human meaning that no music has been able to achieve until now.” It’s hard to know if he was profoundly happy or profoundly sad. Perhaps he was both.

We come at last to Healey Willan: the only composer on my list who was not Canadian by birth, although he spent most of his life in this country. He was born in England, just outside London, in 1880, and established himself in Toronto in 1913, where he passed away in 1968. An accomplished organist and composer, he headed the Theory Department at the Toronto (now Royal) Conservatory of Music, and later taught at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music. However, his most musically significant appointment was at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in 1921, where he conducted and composed for superb choral forces. He was prolific, penning over 700 works in his lifetime, ranging from small motets to full-scale symphonies.

Willan is well represented on several discs, which are mostly devoted to his choral and organ works. Choir and organ are combined on the CD In the Heavenly Kingdom (Naxos 8-557734); and his organ works alone can be heard on Healey Willan Organ Works (Naxos 8.557375). However, I’m most fond of a 1994 release (Virgin Classics 45109) that’s entirely given over to works for a-cappella choir. The disc also gives a good overview of his stylistic inclinations.

It’s often pointed out that Willan owed much to such 19th-century English composers as Parry, Stanford and Stainer, and this is certainly true. From the first track on the Virgin Classics disc, Immortal, Invisible, God only Wise, there’s a tranquil elegance to his style, and his part-writing is as smooth as silk. But two other prominent influences can be heard in the two short masses recorded here: Renaissance polyphony in his Missa Brevis No. 11; and Gregorian chant in his Missa Brevis No. 4. And what of modernism? Willan was cool to many trends in 20th-century music – but there are some adventurous harmonies in Who is She that Ascendeth?, and some juicy sonorities in Rise Up My Love.

While he was alive, Willan was known as “the Dean of Canadian Composers.” Yet towards the end of his long teaching career, he came to be regarded as a dinosaur, and he knew it. However, it didn’t seem to bother him much. “Music has been my chief delight,” he observed, “and if at any time I have been able to share that delight with others, I am content.”

I’m glad to say that none of my chosen composers has fallen into complete neglect. Their music is too good for that, and a small core of committed musicians is keeping their works alive. (Unfortunately, space constraints have prevented me from saying much about these performers. To make amends, I’ll mention two: Toronto’s Esprit Orchestra, which recorded the works of Colin McPhee; and the pianist Christina Petrowska-Quilico, who has done much to make Ann Southam’s music known.)

That’s all well and good – but these six composers should be household names in Canada, like Margaret Atwood or A.Y. Jackson. And while all listeners may not share my views about each and every piece I’ve mentioned, I guarantee there’s something here for everyone. Trust me – have I ever lied to you before?

© Colin Eatock 2011