Monsaingeon is not one of the people I interviewed to for my recent book, Remembering Glenn Gould (see here) – but I spoke to him on the phone today from Paris, and he shared some thoughts about his association with Gould.

BM: I was in Moscow in 1966, and this is where I met Glenn for the first time. He wasn’t there, of course – my meeting with him was through a recording, which I bought in a record shop. It was Bach sinfonias, from a live concert that he had given in Vienna. At the time, I hardly knew Gould’s name, and there were no recordings available of him in Europe.

I was curious to listen to it – and the experience was one of the most significant moments in my life. I knew that behind this great pianist and great musician there must have been somebody quite out of the ordinary. I felt that, through his music, he was saying, “Come and follow me.”

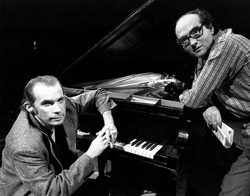

I did this five years later, when I wrote him a letter and got an answer after a few months. He asked me to visit him in Toronto, and that’s exactly what happened. I came to Toronto in July 1972, and we had a wonderful three days of talk and fun and music and work. Already I had in the back of my mind a scenario for a film we could do together – although I was just a young beginner, and had no reputation whatsoever.

This was the start of our extraordinary collaboration, which has lasted to this day.

We began shooting in early 1974, in Toronto, and I spent the year editing the films in Paris. And the four films were broadcast on French television every Saturday night for a month. A year later, we started to work on the scripts for the Bach films, which were made until his demise in 1982. When he died, we had many other projects in mind, which naturally never came to fruition

CE: What was Gould like to work with in the studio?

BM: The amount of time we spent in the studio was nothing by comparison with the preparation and post-production time. We would film over five or six days, after years of preparation. We began preparing for the Bach series in 1976, and we started shooting in 1979.

In Toronto, we had a co-production with the CBC. That was very difficult: the crews that were imposed up on us were not willing to work seriously. I think this accounts for Glenn’s divorce from the CBC. At one point, the two of us had to go to the office and complain about the fact that we were not getting proper collaboration. The man who was the Head of CBC Music in Toronto said, “We are not in a position to accommodate your meticulousness.”

Glenn was friendly with people, and so considerate – and aware of the fact that there were unions, and that we had to respect the rules. But within the rules we wanted to have a sense of working together with a team. Glenn became irritated by the lack of co-operation. I remember one day he offered me a Valium, and said, “That’s the only way to bear with these people.” This is why the collaboration with the CBC was broken, and we did the film of the Goldberg Variations a year later in New York.

Our own collaboration was so smooth, so inspiring and so stimulating that nothing was easier. He was not only a pianist in the films, he was also an actor – and a participant in every aspect of the preparation. He knew exactly what we were doing, and he was very interested in the elaboration of a dramatic structure. With Glenn, every decision was mutual: we’d discuss things for hours, evenings and nights. And when I was in Paris we had daily telephone calls.

CE: Do you have any footage of Gould that the world hasn’t yet seen?

BM: The French films that we did in 1974 were done with chemical film, not video. But at the CBC we worked with video-tape, and they later erased it. So some material was lost, sadly – including a substantial sequence in which Glenn talked about tempos in the Brandenberg Concertos. There’s nothing that was not used in the films that’s still available.

CE: Why do you think the world remains fascinated with Gould, 30 years after his death?

BM: He redefined the role of the performer, and the way people perceive interpretation. He was able to guide the layman in a very brotherly manner through the most intricate scores of music. It was a kind of revelation: no performer at any time has ever managed to lead the listener into the role of a participant. With Glenn, the listener isn’t reduced to the role of a servile admirer.

And his career is still developing. There are new generations who are just as fascinated by Glenn. These are people whose lives have been changed by the contact Glenn was able to establish with his audience. And because there was nothing physical about this contact, his death doesn’t count.

The fact that Gould approached everything in a new light, with a new perception, is so exciting – so much an object of discovery. He gives us the impression that we are exploring the music together with him. These are the reasons why he remains so present today.

© Colin Eatock 2012

RSS Feed

RSS Feed