With this album, Shaham launched Canary Classics.

With this album, Shaham launched Canary Classics. At 42 years, Israeli-American violinist Gil Shaham has everything a classical soloist could want – and more.

First, he has a big international career. In the concert season now drawing to a close, Shaham has played concertos with orchestras in Paris, Milan, Tokyo, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Philadelphia, Montreal and Toronto, and next weekend he’ll be at Helzberg Hall to play Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto of 1935 with the Kansas City Symphony.

In his personal life, Shaham is married to violinist Adele Anthony, and they’re raising three children on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. (He also has a musical sister, pianist Orli Shaham, with whom he sometimes collaborates.)

Shaham also has something else that only a small but growing group of classical musicians can lay claim to: his own record label, Canary Classics. For the last decade, he has released about one CD a year, and he has several more in the works.

It all began one fateful day in 2002, when Deutsche Grammophon, the most prestigious classical recording label in the world, dropped him from its roster. This certainly wasn’t the news he wanted to hear that day, but he now takes a philosophical view of his departure from the German label.

“My end with Deutsche Grammophon was probably a few years in coming,” Shaham said by phone in a recent interview. “The folks at DG and the other major labels would be the first to say that times were already changing 10 years ago, and they’re still changing. The old model no longer fits the market.”

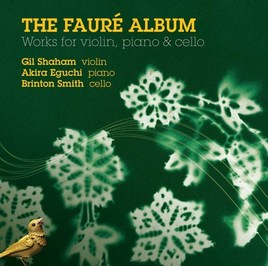

Rather than allowing himself to be sidelined by this turn of events, Shaham launched his own label. His first disc, released in 2004, featured chamber music by French composer Gabriel Fauré, performed by Shaham with pianist Akira Eguchi and cellist Brinton Smith.

With that first disc, Shaham established a business plan that has served him well.

“Our model,” he says, “has always been to make enough of a profit on each recording to fund the next one. So far, the model has worked.”

Shaham notes that changes in technology have made recording music less expensive than it once was and have put recording production within reach of musicians.

“In many ways, technology has set musicians free,” he declares. “When I first started recording, more than 20 years ago, I’d go into a studio full of machines the size of refrigerators. And there were people editing magnetic tape with a razor blade. Now you can do all of that on a laptop. You can get the highest quality audio recordings quite affordably.”

Although not all classical musicians share Shaham’s entrepreneurial spirit, he’s one of several who have taken direct control of their own recordings. Guitarist David Starobin was a pioneer in this field, launching his Bridge Records in 1981.

Cellist David Finckel and his wife, pianist Wu Han, started their ArtistLed label in 1997. Other do-it-yourselfers include cellist Matt Haimovitz (who played in Kansas City last fall), with his Oxingale label; and violinist Lara St. John, who releases discs under the Ancalagon banner.

Several orchestras also have gone the independent route. The San Francisco Symphony’s SFS Media and the London Symphony Orchestra’s London Live are two of the more established labels.

Shaham describes Canary Classics as “a small family business,” and he has kept his recording projects close to home. Almost every Canary release has featured Shaham himself, sometimes with his sister, Orli. There’s also a Canary disc featuring Shaham’s wife as the soloist, in violin concertos by Jean Sibelius and Australian composer Ross Edwards.

This month, Canary released a CD called “Nigunim,” a collection of Jewish music played by the Shaham siblings. The disc also includes music from the film “Schindler’s List” by John Williams and a new piece by Israeli composer Avner Dorman, whose works also have been featured by the Kansas City Symphony and its music director, Michael Stern.

Looking to the future, Shaham hopes to release recordings of the 1930s-era violin concertos he has performed around the world for the last few years.

“We will release a recording of the Berg concerto with the Dresden Staatskapelle on Canary,” he says. “Also, we want to release the Stravinsky concerto with the BBC Symphony and the Barber concerto with the New York Philharmonic. And we’re hoping for more.”

After a decade of running his own record label, what advice would Shaham have for others who were considering the same move?

“I would say you should make sure you’re working with someone who knows the recording world,” he begins. “It has to be a team effort, because there are so many different considerations – more than just producing a master tape. I was lucky to be able to work with some very knowledgeable people who know the industry well.”

There was a time when self-produced recordings might have been viewed as a form of “vanity publishing.” But times have changed, and Shaham certainly doesn’t think there’s anything vain in what he’s doing.

“Ultimately,” he asks, “aren’t all the things that musicians do vanity projects? As long as there’s a demand for my recordings, I’ll keep on making them.”

© Colin Eatock 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed