Was there an intended irony in the title of Tafelmusik’s concert “Mozart and Friends”?

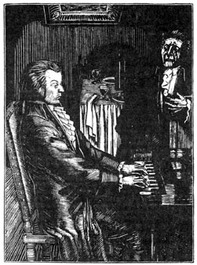

Mozart and Haydn had deep respect for one another, and Ditters von Dittersdorf was a friend, too. But to add Antonio Salieri to the list of Mozart’s “friends” is questionable. No, Salieri didn’t murder Mozart – but the two composers were rivals, and their relationship was rather complicated.

But it was still very much Tafelmusik – led from the front of the first violins by Jeanne Lamon. And the Tafelmusik “house style” was very much in evidence: minimal vibrato, a strong downbeat, and a penchant for filling phrases with little swells of sound.

Salieri was the first composer out of the gate, with his Sinfonia Veneziana, a slender, three-movement piece. The orchestra made neat work of it, playing the outer movements with lively facility, and giving the middle movement a restrained dignity.

However, if Lamon was hoping to overcome popular prejudices against Salieri – widely dismissed as a “mediocrity” – I don’t think she succeeded. This work was merely pleasant, and soon paled in comparison with everything else on the program.

Haydn was represented with his unique Symphony No. 45, known as the “Farewell” symphony. It’s the strange final movement that gives this piece its nickname. In it, Haydn gradually reduces the instrumentation: As the movement progresses, players gradually exit until only two violins are left playing.

The piece was intended as a hint to Haydn’s employer, Prince Esterhazy, that the orchestra wanted to leave the prince’s summer palace and return to town. (When Esterhazy heard it played, he got the message.)

Tafelmusik emphasized this transformation with a performance that began with a brisk and full-bodied sound, and gradually petered out, as players left the stage. As they did so, lights were gradually turned out in the hall, until two violinists were left in the darkness.

As for Mozart, scholars aren’t quite sure if the Sinfonia Concertante in E-Flat Major was written by him or not. Nevertheless, it’s a good piece, and it offers a rare opportunity for four wind players to step forward as a group of soloists. On this occasion, the players were all Tafelmusik regulars: oboist John Abberger, clarinetist Peter Shackleton, hornist Derek Conrod and bassoonist Dominic Teresi.

Of the four featured instruments, the 18th-century clarinet most resembled a modern instrument in sound. Shackleton displayed fluidity and fine intonation, even though his clarinet was, by today’s standards, lacking in keys.

Abberger’s oboe was brighter and reedier than oboes built today, and Teresi’s bassoon had a veiled tone. Both players performed tricky passages with admirable control.

The most “primitive” was Conrod’s horn, a simple coil of brass that neither looked nor sounded much like a modern valved horn. Indeed, it was a little scary to hear him successfully navigate runs up to high notes on an instrument with no moving parts.

Dittersdorf’s contribution to the program – his charming Concerto for Two Violins in D Major – also called forth players from the orchestra.

Violinists Aislinn Nosky and Julia Wedman gave a sweet and perfectly matched performance. The balance and precision of their playing was mirrored in a kind of choreographed movement on stage: It was like a cross between a violin duet and synchronized swimming. I’ve never seen anything quite like it before – but it worked.

© Colin Eatock 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed