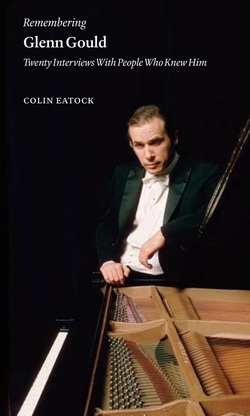

I began this book almost inadvertently. It all started with an interview I did with Glenn Gould’s concert manager, Walter Homburger, back in 2008. (You may read the interview here.) At that time I wasn’t thinking beyond publication of this one interview, in Queen’s University’s venerable journal, Queen’s Quarterly. It was only after the article was published that it occurred to me it could be the beginning of a collection of similar interviews.

There was no lack of people to talk to, in Toronto and elsewhere. I soon discovered that Gould gathered around him an interesting and articulate group of people – and that they usually remember their encounters with Canada’s most famous classical musician as though they last saw him yesterday.

- John Beckwith (composer and fellow student at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory)

- Verne Edquist (piano technician)

- Cornelia Foss (girlfriend)

- Robert Fulford (journalist and childhood next-door neighbour)

- Stuart Hamilton (fellow student at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory)

- Walter Homburger (concert manager)

- Andrew Kazdin (recording technician for CBS Masterworks)

- Anton Kuerti (pianist)

- Jaime Laredo (violinist)

- William Littler (music critic)

- Timothy Maloney (clarinetist and archivist)

- John McGreevy (film maker)

- Margaret Pacsu (CBC broadcaster)

- Tim Page (music critic)

- Stephen Posen (lawyer)

- John Roberts (CBC broadcaster)

- Ray Roberts (personal assistant)

- Ezra Schabas (administrator)

- Vincent Tovell (CBC broadcaster)

- Lorne Tulk (CBC technician)

I’m pleased to say that all 20 of my interviewees offered insightful and heartfelt responses to my prying questions. Yet by no means were they all in agreement in their perceptions of Gould. As a result, what soon becomes apparent in these testimonials are the remarkable contrasts in Gould’s character. He was many things to many people: outgoing or reserved, serious or comical, humble or egotistical, unworldly or down to earth – the list goes on and on.

To paraphrase Walt Whitman, Gould was large and contained multitudes. Perhaps this is why the world remains fascinated with him, 30 years after his death.

© Colin Eatock 2012

RSS Feed

RSS Feed