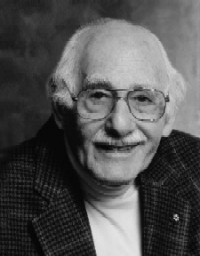

John Weinzweig – who would turn 100 on Monday, if he were still alive – was a Canadian composer of classical music. As well, he taught for many years at the University of Toronto, and was a tireless advocate for contemporary music. (For more information, see here.)

“Stompin’ Tom” Connors was a Canadian singer-songwriter in the country music tradition. He passed away a few days ago, at the age of 77, and admiring obituaries have flooded the Canadian media. (You can read one here.)

I recently recalled Weinzweig’s views on this subject when I noticed a poster that’s currently hanging in the University of Toronto’s Music Library. In large letters, it displays something the “Dean” of Canadian composers (as Weinzweig was dubbed) once said.

“I believe strongly that music has national roots … and our own national identity is going to come about with the music by our own composers.”

As for Connors, his lyrics – to such songs as Sudbury Saturday Night, This Bud’s a Spud, and of course The Hockey Song – drip with maple syrup. Like Weinzweig, Connors saw music as an essential form of national expression. “The singer is the voice of the people / And his song is the soul of our land,” he wrote in his song The Singer.

Yet with these two artists, I can’t help feeling that there was something lacking in their eager self-positioning as voices of Canada. No doubt both men were entirely sincere in their commitment to the country. But despite their determined efforts to make their music as Canadian as they wanted it to be, an essential ingredient was missing.

The central factor that makes Brazilian music Brazilian, Japanese music Japanese, or even American music American is that these musics sound indentifiably Brazilian, Japanese and American.

Neither Weinzweig nor Connors – nor any other Canadian composer known to me – has ever had much success in creating a music that sounds authentically and convincingly Canadian. Canadian music is usually “grafted” on to traditions and practices established beyond our borders, and the Canadian-ness of the resulting music tends to be (in my humble opinion) superficial and compromised.

Weinzweig thought about the issue consciously. But his devotion to international modernism (especially the musical Esperanto of serialism) was sharply at odds with his nationalistic yearnings. Sometimes he wrote pieces that were in some way inspired by Canada, but these inspirations didn’t do much to generate a distinctively Canadian sounding music.

As for Connors, he was so steeped in Anglo-American country and folk music that he may not have given the matter much thought. Yet even as he sang his pointedly Canadian lyrics, his music declared that Canada is really just an undistinguished corner of a larger English-speaking world.

It often occurs to me that the problem of Canadian music not sounding Canadian – because nobody can even imagine what that would sound like – is the elephant in the room whenever the topic of Canadian music arises. And as often happens with an elephant in the room, people try to get around it, in various ways. But a national music is not something that can be boldly proclaimed, arbitrarily invented or simply wished into existence.

The emergence of a distinctively Canadian music – that is Canadian in the same way that Irish music is Irish and Russian music is Russian – will either happen in its own sweet time, or not at all. (If I were a betting man, my money would be on “not at all” – but only time will tell.)

For your listening pleasure, here are YouTube videos of Weinzweig’s Disaccord and Connors’ Tillsonburg. Both works make use of the guitar.

© Colin Eatock 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed