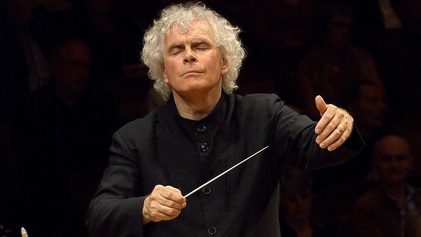

Sir Simon Rattle brought his Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra to Toronto.

Sir Simon Rattle brought his Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra to Toronto. It’s a lesson familiar to many people already, and it goes something like this: great European composers have a clearly traceable lineage: from Bach to Beethoven, to Brahms, to Mahler, and on into the 20th century with Schoenberg and then Boulez. This is the “mainstream” of classical music, a genealogical chart of artistic legitimacy. Just as a nation might have a succession of much-loved kings and little-loved kings, they are all nevertheless kings, by virtue of the crown they inherit.

This view of music history was not so much put forward with words as with the BPO’s programming. Both Tuesday’s and Wednesday’s concerts placed 20th-century modernist composers alongside 19th-century romantics, in a pretty obvious attempt to position the modernists as the rightful inheritors of the romantics’ traditions. Or, to be precise, both programs placed the modernists before the romantics – which felt to me like an “eat your vegetables before dessert” gesture on Rattle’s part.

The first work on Tuesday evening was Pierre Boulez’s Éclat, written in 1965. The piece, scored for a heterogenous ensemble of 15 musicians, bleeped, blooped and blurted along its pontillistic course for about ten minutes, to its final garish chord. Under Rattle’s baton, the BPO played with aplomb, sounding bright and colourful. Éclat was politely received by the audience, as an interesting novelty.

But let’s consider those last two words. The whole edifice of classical music – orchestras, string quartets, choirs, opera houses, and all the rest of it – doesn’t exist because people think classical music is “interesting.” It exists because the music is loved. Any repertoire that would lay claim to legitimate place in the musical pantheon must be ratified by love – and enough love from enough people to achieve a “critical mass.” As for novelty, why does a piece like Éclat sound so novel? More than half a century after it was written, it still sounds like something from another planet, bizarrely impervious to human understanding or assimilation. And I fully expect it will still sound just as bizarre to almost everyone who hears it in yet another half century (if anyone is still listening to it). It will be novel forever.

On Wednesday evening, Rattle forged ahead with his advocacy of modernism, beginning the program with a collection of works by Arnold Schoenberg and his disciples Anton Webern and Alban Berg. And in a “doubling-down” gesture, he chose to present Schoenberg’s Fünf Orchesterstücke, Webern’s Sechs Stucke für Orchester and Berg’s Drei Orchesterstücke as fourteen continuous movements, without pause. Speaking briefly from the stage before his downbeat, Rattle invoked the image of a young Schoenberg facing the dilemma of how to compose in the wake of Mahler’s expansive, tonally distended symphonies. In so doing, he leaned heavily on the idea that, like it or not, atonality was a necessary or inevitable development.

Permit me to now offer my own opinion of Schoenberg. I certainly can’t deny that the man who wrote Verklärte Nacht was a musical genius – but, as the Vicomte de Valmont said in Dangerous Liaisons, “It is often the strongest swimmers who drown.” And as for Berg and Webern, they were not bad composers – they possessed skill, imagination and conviction – but they attached themselves to the wrongheaded idea that tonality could, should and would be overthrown. All three seemed to think that they could not only lead the culture to water, they could also make it drink.

The outpouring of dissonance that filled RTH was as well played as it could have been: the BPO’s performance was both solid and nuanced. Dark, ominous colours were in abundant supply, but there were also moments of frantic energy, dramatic outbursts and even lush eloquence. None of this, sadly, could change the fact that, for the audience, it was impossible to tell a right note from a wrong one. And unlike ten minutes of Boulez, this medley of the Second Viennese School’s greatest hits lasted nearly an hour. I, for one, applauded heartily when it was over because it was over.

Rattle’s mention of Mahler was a reference to that composer’s Symphony No. 7, played on Tuesday evening (after the Boulez). Leading the orchestra from memory, the English conductor shaped the five-movement work as a series of glorious and sublime moments. The BPO made the most of the contrasts inherent in the score – and in this regard, they were abetted by Rattle, who allowed his players to shine in their solos. And even in tutti sections, there was a sense of self-generated agency within the orchestra, as though the musicians played so astoundingly well together by consensus rather than fiat. Sure, Rattle threw them some tricky change-ups in tempo and dynamics along the way – especially in the fourth movement – but his players responded quickly and deftly to every situation.

Wednesday evening’s concert concluded with Brahms’ Symphony No. 2, also conducted by Rattle from memory. Here, especially, the strings glowed with the rich warmth of polished mahogany, and the woodwinds (in the Third Movement) created a bucolic paradise. The final movement was unfailing intense, and a powerful conclusion to the BPO’s visit to Toronto. I doubt I will ever hear a better performance of a Brahms symphony.

I hope this phenomenal orchestra comes back again, as soon as possible. But I also hope they will leave their shopworn ideas about music history, full of “trajectories” and “goals,” at home next time. This grand narrative doesn’t hold up under closer scrutiny, if only because many composers throughout the 20th century chose many different paths. And it’s pretty clear, in the year 2016, that the atonal musical experiment of the last century was exactly that: an experiment – and one that didn’t work out very well, as far as cultural acceptance is concerned.

Instead, I’d like to hear what some 21st-century composers – especially composers who haven’t bought into the modernists’ propaganda about the “inevitable breakdown of tonality” – can do with an orchestra like the Berlin Philharmonic. And more Brahms, please!

© Colin Eatock 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed