Will the stars align for Samuel Coleridge-Taylor? Here’s something I wrote for today’s Houston Chronicle, about a Coleridge-Taylor festival at the University of Houston.

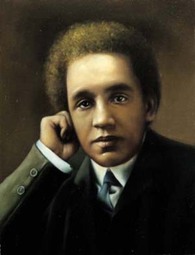

So who was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor?

No, not the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge – but the composer, who died 100 years ago.

During his lifetime, his works were hailed as classical masterpieces, in both Britain and America. But for the past half-century, he’s been largely forgotten.

Largely – but not entirely. One of the few people in the world keeping Taylor-Coleridge’s memory alive is John Snyder, a professor at the University of Houston. He’s organized a two-day Coleridge-Taylor festival this week at the Moores School of Music, with a panel discussion 2 – 5 p.m. Friday in the Choral Recital Hall, and concerts on Friday and Saturday.

As Snyder explains it, he first heard some music by Coleridge-Taylor about 15 years ago – and was immediately impressed with the composer.

“The first thing I heard,” Snyder recalls, “was a recording of his Symphonic Variations on an African Air. It’s a good piece – well constructed and brilliantly orchestrated. There’s an originality to his music, and it’s just plain appealing. He certainly knew how to write a good melody.”

When Snyder saw that the centennial of Coleridge-Taylor’s death was approaching, it seemed like the perfect time to hold a festival.

“Dr. Snyder pushed this idea about five years ago,” says Franz Krager, conductor of the University of Houston Symphony Orchestra, “and the general attitude in the school was, ‘Well, okay, I guess we could do this.’ None of us were very enthusiastic – because we didn’t know Coleridge-Taylor’s music. But the minute we got going, we realized this music is really worth getting into. Now everyone loves it – even the students, and they’re the toughest critics.”

On Friday, Snyder will lead a panel discussion that will include Coleridge-Taylor biographer Jeffrey Green from London, Earl Stewart from the Black Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara, and UH musicologist Yvonne Kendall.

For Friday’s concert, he’s put together a program of chamber music by Coleridge-Taylor: a collection of songs, a clarinet quintet and some piano music – including excerpts from his Twenty-Four Negro Melodies.

And on Saturday, the UH Symphony Orchestra will play Coleridge-Taylor’s Ballade, his Violin Concerto (the violin soloist is Andrzej Grabiec) and his Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast cantata, with the UH Concert Chorale.

The legend of the Iroquois leader Hiawatha was a life-long source of fascination for Coleridge-Taylor. Several of his compositions are based on it – and he even named one of his children Hiawatha.

Of course, Coleridge-Taylor’s musical education at London’s Royal Academy of Music wouldn’t have included indigenous music from America or Africa. And although his father was from Sierra Leone, he was never an influence on Coleridge-Taylor. (His father soon abandoned his English family and returned to Africa.) As a result, Coleridge-Taylor didn’t really know much about what American Indian or African music sounded like.

However, African-American music was a different matter. Coleridge-Taylor heard the Fisk University’s Jubilee Singers, from Nashville, singing black spirituals on a tour to England – and incorporated some of them into his Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano.

By the time Coleridge-Taylor made his first trip to the U.S. in 1904, he was already known and admired by the African-American community. A Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society had been founded in the U.S., which he conducted in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. He was the first black conductor to lead the United States Marine Band – and on a later visit, he also led the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Tragically, his rise to fame was cut short by his early death, from pneumonia, at age 37. Within a few decades his music went into decline.

Snyder is at a loss to account for this fall from popularity.

“There doesn’t seem to be any good reason for it,” he says. “But Bach’s music went into decline for a couple of generations after his death – so if it can happen to Bach, it can happen to anyone.”

Yet Snyder is hopeful a revival is under way. He points out there have been some commemorative performances of Coleridge-Taylor’s music in England this year – including the world premiere of his opera, Thelma. (It was long thought lost, but it was really just misplaced on the wrong shelf in the British Library.)

As well, Snyder notes that in recent years some of Coleridge-Taylor’s works have been released on compact discs.

“There’s an increasing number of recordings – when that happens, it’s not just a flash in the pan. And I hope our festival will contribute to the revival. To my knowledge, our event is the biggest celebration in America of Coleridge-Taylor’s centennial.”

© 2012 Colin Eatock

RSS Feed

RSS Feed