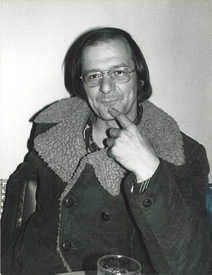

Composer Claude Vivier (1948-1983).

Composer Claude Vivier (1948-1983). Koerner Hall, at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music, is a small venue for a big orchestra. But on Aug. 12, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, under music director Peter Oundjian, shoehorned itself onto the stage to play the closing concert of the Toronto Summer Music festival.

Now in its ninth season, Toronto Summer Music is an annual event of modest proportions: This year’s festival offered a dozen main concerts (plus some informal “shuffle” concerts and student performances), spread out over three weeks. Yet from the beginning, the event has taken a quality-over-quantity stance, presenting chamber and vocal programs by topflight musicians. This summer, the Emerson String Quartet opened the festival; other artists included the Orion and Modigliani quartets, pianist Peter Serkin and soprano Sondra Radvanovsky. For 2014, the festival’s theme was “The Modern Age,” and there was an emphasis on repertoire from the early 20th century.

It was an eclectic and unusual program, with nary a soloist or full-blown symphony in sight. Yet, notably, it did include the only major Canadian composition heard in the festival this year: Orion, by the late Claude Vivier, which opened the concert.

Composed in 1979, Orion is an imposing essay, despite its slender thirteen-minute duration. It’s a starkly dramatic piece, full of ritual and mystery, and, stylistically speaking, it sounds like the love-child of Charles Ives’ Unanswered Question and Carl Ruggles’ Sun Treader. It’s also one of the few Canadian orchestral works to find international traction. Orion has been performed in Berlin and London; in the U.S., it’s been played by the orchestras of New York, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles.

Ounjdian’s interpretation was spacious, with clear control of foreground-background contrasts. It was an effective approach, and the TSO musicians responded by making the most of the vivid colors contained in the score. It was an impressive start to the concert.

Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis proved an ideal vehicle for Oundjian. He has a penchant for the kind of flexibility that works well with music of this sort – and Vaughan Williams is one of his favorite composers. In Oundjian’s hands, the Fantasia had a constant ebb and flow, with long phrases and gradual crescendos. In tutti sections, the TSO strings sounded lush and vibrant. When smaller forces were called for, the orchestra took on a delicate, vibrato-less, slightly nasal tone, suggestive of Renaissance viols.

After the mysticism of the first two pieces, Weber’s Oberon overture had a down-to-earth charm. After an understated opening, Oundjian took his orchestra on a lively, spirited romp.

The closest thing to a symphony on the program was Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances. The performance featured refined playing from the TSO, especially from the woodwind section. However, Oundjian’s approach was more symphonic than dance-like, and here his flexibility was not always a virtue, sometimes robbing the music of rhythmic steadiness. This was especially apparent in the stop-and-start waltz movement. Happily, the closing movement was marked by a clearer and more emphatic sense of tempo and meter.

Finally, the TSO had not one, but two, encores in its back pocket: a brisk third movement from Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 and an effervescent “Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

It’s often said that orchestras play best when on tour: The players are refreshed and inspired by new halls and new audiences. Certainly, the TSO sounded excited and well prepared to take its wares to Europe. I think Europeans will be impressed (and perhaps a little surprised) by what this Canadian orchestra can do.

© Colin Eatock 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed