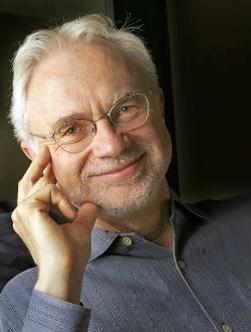

John Adams was this year's featured composer.

John Adams was this year's featured composer. This year marked the tenth anniversary of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s New Creations Festival, held in early March at Roy Thomson Hall. Music director Peter Oundjian launched it a decade ago, with three concerts spread over a week, and it has held true to this format ever since. And while it could be argued that presenting new works in this tightly focused way tends to ghettoize them, the festival has brought a clutch of prominent composers to Toronto – including Tan Dun, Peter Eötvös, and Oliver Knussen – who also help to shape each year’s festival. New Creations has made the TSO a vital part of Toronto’s new music scene.

But the festival also had another strong thread holding it together. It was a big year for concertos and concerto-like works. Five recent pieces for orchestra and soloists offered five different perspectives on the concerto as a 21st-century genre.

For sheer size and scope of ambition, two concertos conducted by Oundjian clearly invited comparison with the greatest works in the tradition. Certainly, that seemed to be the aspiration at the heart of Magnus Lindberg’s Piano Concerto No. 2, played by Yefim Bronfman, and Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Violin Concerto, played by Leila Josefowicz, while the other works were not so firmly attached to the genre’s glorious past.

The Lindberg concerto, which was premiered by Bronfman with the New York Philharmonic two years ago and brought back in January, is jam-packed with big-fisted, virtuosic gestures, recalling the piano concertos of Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Ravel, and others. Stylistically, the piece clings to the edge of tonality – and there are times when the Finnish-born composer’s orchestral textures are thick and heavy to the point of constriction. But these give way to refreshingly clear and crisp passages, and even to delicacy in the cadenza writing. Bronfman made the most of all these contrasts, to tremendous effect. Yet for all its grandiloquence, the concerto was undermined by the ephemeral fluidity of its thematic material. Perhaps for this reason, the result was more impressive than satisfying.

Much the same could be said of Salonen’s Violin Concerto, on Mar. 5. Like the Lindberg, it was played by the soloist for whom it was originally written. (The Canadian-born Josefowicz has also recorded it, Salonen conducting, for Deutsche Grammophon.) Once again, the scale of the work is expansive, and the orchestration is rich and fascinating. Josefowicz brought an arresting mastery to the stage, and her performance cut through the TSO like a razor. Yet there is too much “muchness” in the piece, and its tonally modernist outpourings tended to pall on the ear.

The Icelandic composer Daniel Bjarnasson was represented by Bow to String, a work that began its life as a recording-studio creation: a piece for multiple, overdubbed cellos. On the March 5 concert, Bow to String was presented in the composer’s arrangement for chamber orchestra, with the original cellist – Saeunn Thorsteinsdóttir, also from Iceland – appearing as the (discreetly amplified) soloist. Adams, who has taken Bjarnsson under his wing, conducted. The 15-minute piece, which can be sampled here, is an engaging, post-modern mix of angry dissonance and serenely Bach-like harmonies. Above it all, Thorsteinsdóttir soared.

The concert of Mar. 7 offered two substantial concertos. Canadian composer Vincent Ho’s City Suite, for cello (again, amplified) and orchestra was, I believe, the most successful work heard in this year’s festival. The soloist was Toronto-based Shauna Rolston, and the TSO composer-adviser Gary Kulesha was on the podium.

Rolston performs on a carbon-fiber cello, possibly because she plays with such energy that a wooden instrument would soon be reduced to kindling. At least, that’s the impression she gave during her ferociously brilliant performance of City Suite.

The four-movement piece is harmonically wide-ranging and overflowing with striking ideas. There are slithery phrases in the cello suggestive of the sound of a Chinese erhu, furious virtuosic outbursts rising from the depths of the instrument to its stratosphere, and even a jazzy little tune in the final movement. Ho’s orchestration was unfailingly effective, not only in the big tutti passages, but also when he limited himself to just a few instruments. It would be a fine and worthy thing if City Suite attracted the interest of orchestras beyond Canada’s borders.

The other concerto on Mar. 7 was Adams’s Absolute Jest for orchestra and string quartet. For the occasion, the St. Lawrence String Quartet made an (amplified) appearance, and the composer conducted. In his introductory remarks, Adams described Absolute Jest as a “riffing” on Beethoven, full of excerpts from various scherzo movements, cleverly woven into the composition. Indeed, they were the best parts, and if Adams had learned from Beethoven that brevity is the soul of wit, the piece might have been shorter and better. Adding to the performance’s misfortunes was the raw aggressiveness of the quartet, giving the impression that the orchestra and the soloists were in some kind of competition with each other.

Absolute Jest was one of three pieces by Adams in this year’s New Creations Festival. On Mar. 1, Oundjian led Adams’ Doctor Atomic Symphony, derived from his opera about Robert Oppenheimer and the first atomic bomb. The single-movement work vividly recalls the opera, especially the aria “Batter My Heart, Three-Person’d God,” played with vocal lyricism by TSO trumpeter Andrew McCandless. And on Mar. 5, Adams conducted Slonimsky’s Earbox, a glittery showpiece that leans in the direction of Stravinsky at times. The TSO made neat work of its challenges.

There was more music, all by Canadians. Kevin Lau, currently the TSO’s affiliate composer, wrote Down the Rivers of the Windfall Light for the Mar. 1 concert, given its premiere under Oundjian. Like Ho, Lau is a musical magpie, taking his inspiration wherever he pleases. But although Down the Rivers of the Windfall Light begins well, with a pastoral tone suggestive of Vaughan Williams, it soon takes off in all directions, as though cramming as many influences as possible into the score were Lau’s goal.

On Mar. 5, Adams conducted Lineage by Zosha Di Castri, another composer he is promoting these days. Di Castri’s piece was the strangest work in the festival, thanks in part to her fondness for microtones. And on Mar. 7, Brian Current’s Three Pieces for Orchestra was led by Oundjian. All of them are animated essays in orchestral color. The most successful is the third, with its driving rhythms, pressing toward a dramatic conclusion.

© Colin Eatock 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed