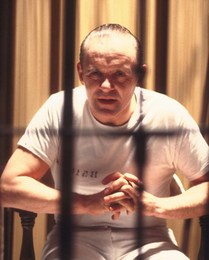

He’s just had a concert of his works – played by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, no less. And although I’ve never heard a note of his music, I’m prepared to make a bold prediction about its critical reception: no matter what it sounds like, it won’t be taken very seriously. Anthony Hopkins can do a lot of things – but he cannot make a name for himself as a composer. He is simply too well known as an actor for the world to think of him as anything else.

Sometimes these people are performing musicians: the pianist Marc-André Hamelin, the flautist Robert Aitken and the conductor Bramwell Tovey (to give three Canadian examples) also compose. While this is perhaps uncommon today, it didn’t use to be. A couple of centuries ago, performers were expected to also write music.

But nowadays it seems that many who try to do both pay a price for their well-roundedness. For their efforts, they may be dismissed as vain, pretentious and self-indulgent. They may be viewed as “taking advantage” of their stature as performers to promote their music – or, conversely, as less than entirely committed to their performing careers.

Composers today sometimes find other music-related ways of earning a living. I’ve known some radio producers who were also composers – also a few music critics, librarians and arts administrators. Still others make a living by doing things that are entirely unrelated to music: everything from landscaping and driving a taxi to practicing law and medicine.

A kind of faux professionalism has descended upon the compositional world: a set of unspoken rules to designed enforce the preposterous idea that anyone who is “really” a composer can’t, doesn’t and won’t do anything else for a living.

I can remember some years ago meeting a young, ambitious composer who was only too happy to tell me about the performances he had received and the commissions he was working on. But when I asked him what he did for a living, he became vague and evasive. It took quite a bit of prodding to get him to admit that he worked as a bookkeeper in his father’s business, renting out machinery used in the construction industry. He was obviously afraid I would think less of him for having such an uncool day job. (I didn’t.)

The one major exception, it seems, is teaching music composition at a university or conservatory. In fact, this line of work may actually enhance a composer’s stature and reputation. However, it must be music composition that is taught: the composer who gives lessons in performance, or teaches music theory or history, may be viewed with suspicion.

So who made these rules, and why? What good purpose do they serve? And why is the musical world so willing to abide by them?

Alexander Borodin was a scientist by trade, back in 19th-century Russia. But if he lived today, would he have “gotten away” with also being a composer?

© Colin Eatock 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed