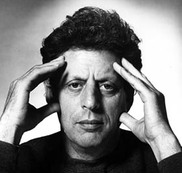

I’m glad I wasn’t there – not because I disapprove of the OWS movement, but because the “human microphone” thing they do doesn’t seem to work very well. It’s hard to make out much of what Glass is saying.

When righteousness (When righteousness)

Withers away (Withers away)

And evil (And evil)

Rules the Land (Rules the Land)

We come into being (We come into being)

Age after age (Age after age)

And take visible shape (And take visible shape)

And move (And move)

A man among men (A man among men)

For the protection of good (For the protection of good)

Thrusting back evil (Thrusting back evil)

And setting virtue on her seat again. (And setting virtue on her seat again.)

The text is from Satyagraha.

I can’t help thinking that the crowd, repeating the short phrases in a kind of chant, sounds like some minimalist compositions I’ve heard. Could this be an inspiration for a new Glass opera in the making? Or does the contemporary, political, context place it squarely on John Adams’ turf?

I also can’t help wondering if the protests – while not exactly directed at the Met and the people who attend its performances – raise the question of where opera and classical music stand within North American culture today. Does opera “belong” to the 1 percent? Do most people think it does? Should they?

It would be an over-simplification to answer these questions with either a yes or a no. First of all, classical music has its own internal 99/1 percent division. The vast majority of classical musicians earn modest incomes, sometimes with precarious job-security and little in the way of benefits. Then there’s the other 1 percent: the conductors and top opera stars raking in a few million dollars a year.

There’s also the question of who’s paying the bills. In the USA (and, to a lesser extent, in Canada) arts organizations must look to private donors to fund their activities. This can lead to situations where some donors may feel that they have acquired proprietary rights over the art in question.

I recall the horrid idea, floated by the arts patron Alberto Vilar, some years ago, that he should make a curtain-call after an opera production he funded. “What makes me less important than Plácido Domingo?” he reportedly asked in all seriousness. (Convicted fraudster Vilar certainly won’t be making any curtain-calls from his current address, a US prison, any time soon.)

The downside of private patronage is that it can have the sad effect of re-enforcing the idea that art is “elitist”: if rich people are paying for it, then it must be for them. This problem was well articulated in an editorial that appeared in London’s Guardian newspaper some months ago. The writer, Andrew Haydon, was responding to the proposal that the UK’s government should cut back on state funding, while encouraging, through tax-relief, more donations to the arts from the wealthy.

“The final outcome of this policy,” he pointed out, “is a shift from the arts being something of which we as a country could be proud, to something for which we-as-arts-goers must thank some rich people.”

Well said!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed