He’s the technological wizard who invented the piano “re-performance.” A re-performance involves using computers to extract complex performance data from an old piano recording, and then programming a Yamaha Disklavier Pro piano (essentially a high-tech player piano) to play it back.

Five years ago, I attended a live demonstration of a re-performance based on Glenn Gould’s 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations. (You can read what I wrote about the event at the time here.) Since then, Walker has constructed re-performances of Art Tatum, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Oscar Peterson. These are all available in CD form. (See here.)

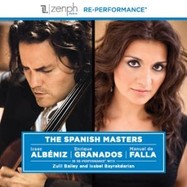

And now Zenph has released a disc that includes Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados and Manuel De Falla playing their own music at the piano. But he’s taken his idea one step further, with the addition of living, breathing musicians to the mix. On this new disc, we can hear De Falla’s Siete Canciónes Populares Españolas performed by the composer – and sung by soprano Isabel Bayrakdarian and played by cellist Zuill Bailey.

However, the original soprano, who collaborated with De Falla in this 1928 recording, is nowhere to be heard. (The press release doesn’t say who she was, but I suspect it was Maria Barrientos. And I also expect she would be mightily displeased: Spanish sopranos don’t take this sort of thing lightly.) The piano part has been isolated and extracted, enabling the live musicians to perform in a studio, along to a Disklavier playing itself (so to speak), exactly as De Falla played.

In taking this approach, Zenph has inverted the traditional power-dynamic between soloist and accompanist. Here, we have the (dead) pianist dictating precise terms of interpretation to a (living) soprano and cellist. Of course, in an ideal collaboration, nobody is should be “dictating” anything to anyone else.

You can hear audio-clips of this strange approach to music-making here. The examples are too short to draw any firm conclusions about whether it works musically or not, so I shall refrain. However, I will say this: Walker & Co. are clearly a bunch of geniuses – but I find this devotion to musical necromancy more than a tad creepy.

As well, his work tends to underscore and reinforce a cultural problem. Today, the classical music world is backward looking to a fault: we love the past too much, often to the detriment of the present. And just when you might think that the culture of classical music has become as fixated on its own history as it could possibly be, John Q. Walker comes along with an elaborate way to make it even more backward looking.

© Colin Eatock 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed